I love a good 4-way. Everyone slows down, stops, and acknowledges those at the crossroads. At a slower pace, you can make eye contact, be polite and motion another to go ahead of you. Others become human.

When I visit the UK with my husband, I am always anxious at the roundabout. Cars whiz by, no eye contact, no recognition of drivers. My heart races, my mind wishes we would all slow down. If we do slow down, the other drivers get impatient, honk and make hand gestures. They have places to go … in a hurry. They have no time for niceties.

Today, our world in the US is the paradox of these two modes of traffic. We once loved our 4-ways when times were slower. Now, we are installing roundabouts. We want to whiz through life, cut the drive time. Just let us flow.

Starbucks and its #RaceTogether campaign made the mistake of trying to create an organic 4-way that functioned like a roundabout. The initial town halls (the prototype) were the 4-ways. Those work. We have time to sit and discuss. But in the retail cafe business, folks just need their coffee … fast. Roundabout. I love a good tea, and Starbucks is often my go-to, but during this, I took the detour.

This week, let’s reinstall the 4-way. I am attending the American Adoption Congress meeting and slowing down … stopping. The beauty of a meeting like this is that all parts of the triad are present. We have the ability to see the intersectionality up close.

In one session, an adoptee mentioned the pain of domestic, same race adoption. Strangers at a funeral were fishing for similarities in her features to her parents. Obviously, for her the amplification of her differences as an adoptee colored her interactions. The funeral brought triggers. I can see that.

Another domestic adoptee mentioned the pain of people saying there is no difference between an adopted child and a biological child in a single family. While she had been matched racially to her parents, she mentioned that she couldn’t see herself in the physical features of her parents like a biological sibling can.

All these voices are valid. Mine may not synch with theirs, but we have common threads … the pain of loss. I wish my fellow conference-goers time to slow down, reflect and respect.

P.S. Sometimes I get carried away in person; my emotions can mask my intentions. Please remind me to SLOW. DOWN.

27 March 2015

24 March 2015

#DearMe, speak your truth.

I am truly grateful for the community of adoptees.

When I first became aware of the #DearMe campaign, I posted a suggestion on Facebook that I thought this campaign and its work with young people reflected the mission of Dear Wonderful You from the AnYa Project. I also suggested that we make our own videos to support our younger selves.

Thanks to Diane Christian of the AnYa Project, Kimberly McKee of the Korean American Adoptee Adoptive Family Network (KAAN) and Amanda Woolston of The Lost Daughters for bringing this small dream to fruition.

For all the beautiful young adoptees out there:

19 March 2015

The Twinkie Chronicles … Facebook Follies.

Over the holidays, I hosted my Puerto Rican cousins in balmy Wisconsin. After promising them snow, I failed. It was the warmest, snow-free Christmas since our move to Madison. We, of course, had moments of laughter and took lots of selfies!

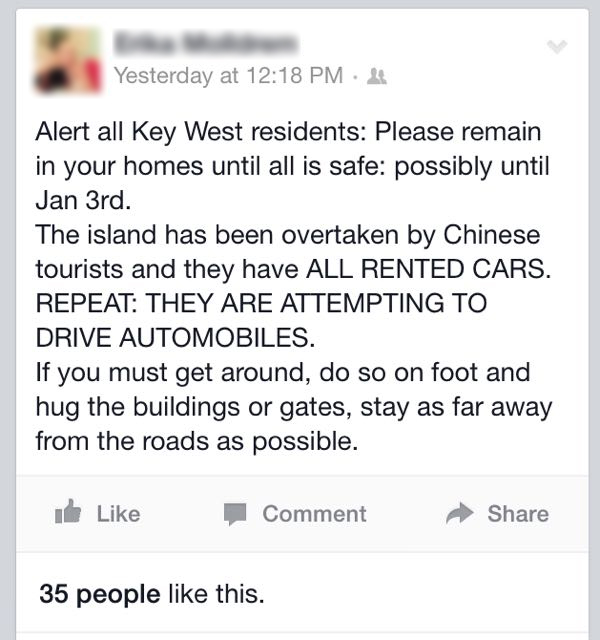

Wow. Facebook can be such a downer and a life lesson.

On the advice of my dad, I took my cousin shopping. A Gonzo tradition … family shopping. We took everyone to the shops. Even here, I saw the underlying racism. My cousins speaking Spanish or broken English brought employees lurking around the corners … while I tried to establish normalcy by speaking loudly in English and flashing my proxy-white-privilege card.

We had a grand time catching up and FaceTiming my dad.

Coming down from my family high, I checked my facebook feed. And …

Labels:

#TwinkieChronicles,

bullying,

culture,

facebook,

Korea,

Korean,

privilege,

racism,

stereotypes

16 March 2015

The Twinkie Chronicles … Bullies Galore

“Stop dragging your feet.”

“I wish you would wear clothes that fit you.”

“Don’t slump. Stand up tall with your head up. You are making yourself out to be a victim.”

These words from my mother are replaying in my head, as I watch my son move into his high school days. When you are belittled, you try to make yourself smaller. My mother did what she thought was right and helpful; she also supported me when I dyed my hair and cut it wildly to distract from my otherness. I find myself doing the same for my son, and I am sure one day, he will revive my missteps.

I worry that my son will inherit the low self-esteem from my young adult days.

Back then, I believed that no one would want me, except to use me. I had dated men, only to have them dump me for a blonder, whiter version of myself. When I turned 21, the man I thought I would marry, became a man with a secret life and a fiancée in Appleton, WI. While I had lived my life thinking I would use men before they used me, I just didn’t. I knew my Asian self wasn’t good enough “to hold a man down” in Tennessee. I was masquerading as a white person but always reminded that I was another kind of other.

I heard:

“Do something with your hair. It’s so greasy looking.” Because I couldn’t achieve the Aqua Net Big Hair of the 1980s.

“Does your cooter look different, like is it slanted from side to side?”

“Can you EVEN see with your eyes like that?”

“So, that guy who brought you to the prom … did your parents hire him as your escort?” My high school companion in those days was a Wake Forest college man I met while waiting tables at the Cracker Barrel. He was the only person I could write honestly and expect an honest, kind answer back.

And then, there were the misnomers: “Chinese,” “Cambodian Swamp Rat,” “Jap,” “Dirty Diaper Food Eater” …

I kept many of these things from my family. When I returned home for my father’s funeral, my cousin asked me why I didn’t return to Tennessee every year. I had to be honest with her and tell her of my discomfort and how I felt traumatized when I came home. There were too many bad memories. I felt inadequate and strange in my hometown. She was floored. “I never knew this. Who would say such things to you?!” she asked. I told her that some things were said to me at church. Again, she was floored.

My white family members insist they do not see my color or race. I know they don’t and when I was very young, I tried to ignore that fact too. It worked just fine when the safety of their whiteness was within earshot, but that safety inevitably left with them.

Let’s fast forward. Today, we think we have it better. We do not. The racist comments are now more politically correct, but they are still racist. The Twinkie has begat another Twinkie. This one is more authentic but nonetheless still viewed as Asian.

We moved to liberal, “most livable” Madison, WI, in 2009.

My kids quickly became aware of the prevailing air of racism. At first, I thought they would be immune, that their father’s whiteness would save them. But just like their Twinkie mother, my Asian genes would betray them as well.

I recently found this drawing of my son’s day tucked away in his papers.

Trying to combat racist bullying is hard. Without proof (a witness or video footage) there is little the school can do to stop it. My son returns home with holes in his pants, bruises and anger. He is fearful of school.

My son’s bullies come in all colors; mine did too. I always said, “Shit rolls downhill, and I am the smallest minority.”

For me, the biggest wounds came from whites. Their superiority and power scared me. They ruled the hallways and campuses. They still do. White America continues to beat people of color down, pit us against one another. This fact was emphasized in the first episode of Fresh Off the Boat, in this line spoken by Walter, the only black kid in school, “You’re at the bottom now; it’s my turn.”

Why must anyone be at the bottom?

“I wish you would wear clothes that fit you.”

“Don’t slump. Stand up tall with your head up. You are making yourself out to be a victim.”

These words from my mother are replaying in my head, as I watch my son move into his high school days. When you are belittled, you try to make yourself smaller. My mother did what she thought was right and helpful; she also supported me when I dyed my hair and cut it wildly to distract from my otherness. I find myself doing the same for my son, and I am sure one day, he will revive my missteps.

I worry that my son will inherit the low self-esteem from my young adult days.

Back then, I believed that no one would want me, except to use me. I had dated men, only to have them dump me for a blonder, whiter version of myself. When I turned 21, the man I thought I would marry, became a man with a secret life and a fiancée in Appleton, WI. While I had lived my life thinking I would use men before they used me, I just didn’t. I knew my Asian self wasn’t good enough “to hold a man down” in Tennessee. I was masquerading as a white person but always reminded that I was another kind of other.

I heard:

“Do something with your hair. It’s so greasy looking.” Because I couldn’t achieve the Aqua Net Big Hair of the 1980s.

“Does your cooter look different, like is it slanted from side to side?”

“Can you EVEN see with your eyes like that?”

“So, that guy who brought you to the prom … did your parents hire him as your escort?” My high school companion in those days was a Wake Forest college man I met while waiting tables at the Cracker Barrel. He was the only person I could write honestly and expect an honest, kind answer back.

And then, there were the misnomers: “Chinese,” “Cambodian Swamp Rat,” “Jap,” “Dirty Diaper Food Eater” …

I kept many of these things from my family. When I returned home for my father’s funeral, my cousin asked me why I didn’t return to Tennessee every year. I had to be honest with her and tell her of my discomfort and how I felt traumatized when I came home. There were too many bad memories. I felt inadequate and strange in my hometown. She was floored. “I never knew this. Who would say such things to you?!” she asked. I told her that some things were said to me at church. Again, she was floored.

My white family members insist they do not see my color or race. I know they don’t and when I was very young, I tried to ignore that fact too. It worked just fine when the safety of their whiteness was within earshot, but that safety inevitably left with them.

Let’s fast forward. Today, we think we have it better. We do not. The racist comments are now more politically correct, but they are still racist. The Twinkie has begat another Twinkie. This one is more authentic but nonetheless still viewed as Asian.

We moved to liberal, “most livable” Madison, WI, in 2009.

My kids quickly became aware of the prevailing air of racism. At first, I thought they would be immune, that their father’s whiteness would save them. But just like their Twinkie mother, my Asian genes would betray them as well.

I recently found this drawing of my son’s day tucked away in his papers.

Trying to combat racist bullying is hard. Without proof (a witness or video footage) there is little the school can do to stop it. My son returns home with holes in his pants, bruises and anger. He is fearful of school.

My son’s bullies come in all colors; mine did too. I always said, “Shit rolls downhill, and I am the smallest minority.”

For me, the biggest wounds came from whites. Their superiority and power scared me. They ruled the hallways and campuses. They still do. White America continues to beat people of color down, pit us against one another. This fact was emphasized in the first episode of Fresh Off the Boat, in this line spoken by Walter, the only black kid in school, “You’re at the bottom now; it’s my turn.”

Why must anyone be at the bottom?

Labels:

#TwinkieChronicles,

bullying,

high school,

Madison,

parenthood,

race,

racial insults,

racial slurs,

relationships,

son,

Tennessee

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)