This week, my father’s birthday came and went.

Birthdays, as you know, are very difficult for me. My birthday is a fabrication, a lie, a secret that only my original mother could reveal.

My father’s birth certificate says that he was born on September 20, but in fact, he was born on September 21. The story, as told by my grandmother (Abuelita), goes like this …

On the day my father was born, my grandfather was overjoyed, so much so he celebrated to utter inebriation. When he finally appeared to register my father’s birth at the town office, he gave the wrong date to the registrar.

My father honored his mother’s words and her story. He knew she would never forget the day he entered the world. His connection to her was sealed that very 21st of September. So, throughout my father’s life, he used September 21 as his birthdate.

This year, the sorrow of losing him mixed with the comfort of knowing him. His life was one of suffering, silliness and sweet moments with his family. I hope to have as many of those moments, whatever they hold, as he did.

As I walk the streets of Seoul, just as he did in 1965 and 1966, I think of him eating rice for breakfast and sweating as he ate kimchi.

Showing posts with label father. Show all posts

Showing posts with label father. Show all posts

23 September 2015

Your Daddy’s Gone

Labels:

Abuelita,

Abuelo,

birth mother,

birth story,

birthdate,

birthday,

Daddy,

father,

original mother,

sorrow

05 September 2015

Korea: The Ghost Walk

We are in a sea of me’s. Everywhere, people walk about not knowing the scrutiny I subject them to.

Anyone could be a relative … a parent, a sibling, a grandparent, an aunt, an uncle or a cousin. But none of us know it. We are secrets wandering and searching for the key to the box that will set us free to love those who are biological relations.

I think of my domestic adoptee friends in the United States and realize the torture they have felt from the very beginning. You are a stranger to those who share your DNA. You study those who have your traits and long to know if there is a connection between you … an imaginary thread that connects you.

In their first week as Koreans in Korea, my children are learning this as well. My goal this week was to take them to the haunts of my last trip … places that bring me comfort and center my soul. For the most part, it has been a joy to revisit the wonder I felt and watch my children feel the same.

We visited Insadong, Gangnam and Hapjeong. By their third day, they seemed comfortable.

Yet, their minds were playing similar earworms. After the trip to Gangnam, my daughter said, “I just saw a man that looked like Papito.” She is searching for my half-brother, an uncle that would bring her Papito back. Just seeing his features or his mannerisms in a Korean man comforts us. If we found him, we would come full circle in this crazy, complicated thing called adoption.

My son is quieter and shares when it is overwhelming. When a middle-aged man in the Burger King took his tray to clean up, he shared that he felt a connection to him. He recently had a job as a bus boy, but he was struck by the fact that this man was older and doing his former job.

Here we talked about how I felt connection to them as an adoptee … how my imagined story of poverty and desperation lead to my adoption … how I imagine that these “others” are me.

Anyone could be a relative … a parent, a sibling, a grandparent, an aunt, an uncle or a cousin. But none of us know it. We are secrets wandering and searching for the key to the box that will set us free to love those who are biological relations.

I think of my domestic adoptee friends in the United States and realize the torture they have felt from the very beginning. You are a stranger to those who share your DNA. You study those who have your traits and long to know if there is a connection between you … an imaginary thread that connects you.

In their first week as Koreans in Korea, my children are learning this as well. My goal this week was to take them to the haunts of my last trip … places that bring me comfort and center my soul. For the most part, it has been a joy to revisit the wonder I felt and watch my children feel the same.

We visited Insadong, Gangnam and Hapjeong. By their third day, they seemed comfortable.

Yet, their minds were playing similar earworms. After the trip to Gangnam, my daughter said, “I just saw a man that looked like Papito.” She is searching for my half-brother, an uncle that would bring her Papito back. Just seeing his features or his mannerisms in a Korean man comforts us. If we found him, we would come full circle in this crazy, complicated thing called adoption.

My son is quieter and shares when it is overwhelming. When a middle-aged man in the Burger King took his tray to clean up, he shared that he felt a connection to him. He recently had a job as a bus boy, but he was struck by the fact that this man was older and doing his former job.

Here we talked about how I felt connection to them as an adoptee … how my imagined story of poverty and desperation lead to my adoption … how I imagine that these “others” are me.

13 July 2014

Fear of Being Korean

Every time I look into my children’s eyes, I see pieces of me that I feel I do not know. In August, I journey to Korea with the help of G.O.A.’L, a Korean organization of adoptees who advocate for other adoptees.

I love finally having a physical connection through my children, but I struggle. I don’t want to make it about me. They are their own people. They are entitled to their own identities.

That said, as they have gotten older, they do question, and the tie to me is more evident. They suffer the ambiguity that I feel; they question this unknown family because frankly, it comes up almost every time we enter a clinic or hospital.

We are working through all this at a faster rate than I expected. The trip to Korea is in 43 days. My children are reluctant about my trip. They fear something … losing me … losing Papito (my father) … losing themselves in a family they want to know but are afraid to know.

I feel the same. I have had questions for so long, they live in my mind like all the other nerves that function as a part of my being alive. I have grown accustomed to them and kept them quiet for fear of hurting my parents. However, what I know now as an adult is that my father has always wanted this for me.

He wanted me to know the culture and history of Korea. He wanted me to know the food, the language and the customs. Yet, rural Tennessee was not the place for such knowing. Tennessee is a place of survival … a place to cherish kin and the Bible.

Once more, I see more clearly my father’s Puerto Rican culture was suppressed there. He jokes that when patients at the hospital where he works say, “You got an accent,” he retorts, “I didn’t have one until I got here.”

I see him feeling the ambivalence of being Puerto Rican, yet not … being Tennessean, but not. He knows too well my fears, and I take comfort that whatever happens in August will never break the tie I have to my family at home.

But I fear being Korean. I fear being Korean yet a stranger in my homeland. I fear being Korean but unable to converse with my Korean family. I fear being Korean because that might mean I am less Puerto Rican. I fear being Korean, but not recognizing the part of me that has tormented me my entire life … the part that kept me separate from others … the part that made me different … the part that elicited prejudice.

When I said I was “Korean, not Chinese” as a child, I had no idea how complicated that was.

I love finally having a physical connection through my children, but I struggle. I don’t want to make it about me. They are their own people. They are entitled to their own identities.

That said, as they have gotten older, they do question, and the tie to me is more evident. They suffer the ambiguity that I feel; they question this unknown family because frankly, it comes up almost every time we enter a clinic or hospital.

We are working through all this at a faster rate than I expected. The trip to Korea is in 43 days. My children are reluctant about my trip. They fear something … losing me … losing Papito (my father) … losing themselves in a family they want to know but are afraid to know.

I feel the same. I have had questions for so long, they live in my mind like all the other nerves that function as a part of my being alive. I have grown accustomed to them and kept them quiet for fear of hurting my parents. However, what I know now as an adult is that my father has always wanted this for me.

He wanted me to know the culture and history of Korea. He wanted me to know the food, the language and the customs. Yet, rural Tennessee was not the place for such knowing. Tennessee is a place of survival … a place to cherish kin and the Bible.

Once more, I see more clearly my father’s Puerto Rican culture was suppressed there. He jokes that when patients at the hospital where he works say, “You got an accent,” he retorts, “I didn’t have one until I got here.”

I see him feeling the ambivalence of being Puerto Rican, yet not … being Tennessean, but not. He knows too well my fears, and I take comfort that whatever happens in August will never break the tie I have to my family at home.

But I fear being Korean. I fear being Korean yet a stranger in my homeland. I fear being Korean but unable to converse with my Korean family. I fear being Korean because that might mean I am less Puerto Rican. I fear being Korean, but not recognizing the part of me that has tormented me my entire life … the part that kept me separate from others … the part that made me different … the part that elicited prejudice.

When I said I was “Korean, not Chinese” as a child, I had no idea how complicated that was.

Labels:

ambiguity,

biological child,

biological parents,

children,

Daddy,

family,

father,

fear,

G.O.A.’L.,

identity,

Korea,

Korean,

Puerto Rican,

return,

Tennessee

29 May 2014

The Lengths of Loyalty

At this moment, my father is intubated and riding in an ambulance to Knoxville, Tennessee. This is the man who I highlighted in this tweet.

This tweet came about after my last conversation with my father about my adoption search. As always, he reassured me and punctuated my right to know about my original country and family.

Loyalty is a legacy. While I had discussed my search with my father many times, my husband wanted me to discuss my open search with my father one more time. My husband feared that such actions would hurt my father.

I knew this to be untrue. Too many times, my father and I had discussed the possibility of my search. Books on Korea, his Korean dictionary, his affinity for Korean food were shared with me. I have never felt that I was not his or he mine. But loyalty works its way into my entire family.

Earlier this year, as my daughter was lamenting how far we are from family, she sighed and said, “Mom, I wish I had cousins.” I, of course, began rattling off the names of my sister’s daughter and my sister-in-law’s children. My daughter said, “No, I meant genetic cousins, like in Korea.”

And yet, after our visit to Puerto Rico, my daughter’s loyalty began to show.

“I want to know the heritage (Korean), but I don’t want to know my genetic family. I have cousins already. You can’t neglect the family you have. I don’t need to be blood-related to have family,” she told me.

I asked her how she felt in Puerto Rico.

“I felt out of place at first … as a different race. But then, I realized they (the Puerto Rican family) are enough. What if they (my original family) don’t want to find you? What if they don’t like you or are bad? I don’t want to see you hurt,” She continued.

Obviously, the media, adoption agencies and some adoptive parents reinforce this idea of “being loyal.” Adoptees are asked why we can’t be “grateful.” We are told that our adoptions are “gifts.” Perhaps it is a level of guilt that all families have. Guilt, loyalty and love are all wound up in the fabric of family.

Take for example, the movie, August: Osage County. I saw the pervasiveness of guilt and loyalty spill out in these quotes:

Seriously, I have THE. BEST. DAD. EVER.

What you say? You do? Uh, NO.

Te amo, Papito.

#adoptee

— mothermade (@mothermade) May 21, 2014

This tweet came about after my last conversation with my father about my adoption search. As always, he reassured me and punctuated my right to know about my original country and family.

Loyalty is a legacy. While I had discussed my search with my father many times, my husband wanted me to discuss my open search with my father one more time. My husband feared that such actions would hurt my father.

I knew this to be untrue. Too many times, my father and I had discussed the possibility of my search. Books on Korea, his Korean dictionary, his affinity for Korean food were shared with me. I have never felt that I was not his or he mine. But loyalty works its way into my entire family.

Earlier this year, as my daughter was lamenting how far we are from family, she sighed and said, “Mom, I wish I had cousins.” I, of course, began rattling off the names of my sister’s daughter and my sister-in-law’s children. My daughter said, “No, I meant genetic cousins, like in Korea.”

And yet, after our visit to Puerto Rico, my daughter’s loyalty began to show.

“I want to know the heritage (Korean), but I don’t want to know my genetic family. I have cousins already. You can’t neglect the family you have. I don’t need to be blood-related to have family,” she told me.

I asked her how she felt in Puerto Rico.

“I felt out of place at first … as a different race. But then, I realized they (the Puerto Rican family) are enough. What if they (my original family) don’t want to find you? What if they don’t like you or are bad? I don’t want to see you hurt,” She continued.

Obviously, the media, adoption agencies and some adoptive parents reinforce this idea of “being loyal.” Adoptees are asked why we can’t be “grateful.” We are told that our adoptions are “gifts.” Perhaps it is a level of guilt that all families have. Guilt, loyalty and love are all wound up in the fabric of family.

Take for example, the movie, August: Osage County. I saw the pervasiveness of guilt and loyalty spill out in these quotes:

“Mama was a mean nasty lady. That’s where I get it from.”

“Smug little ingrate … ”

“Your father was homeless for six years!”

“Stick that knife of judgement in me. You don’t choose your family!”

I am realizing that we all have this level of loyalty. My father’s loyalty to me is that he wants to shield me from hurt too. Just before my mother and my grandmother died, both my mother and my father withheld their medical conditions from me. They wanted me to enjoy my life and not stress about things they felt were out of our control. But in the end, the white lies hurt more. I couldn’t understand why they wouldn’t tell me.

Now, I realize so much more. I have that loyalty. The loyalty to lie. The loyalty to protect. The loyalty to love.

Labels:

adoption,

adoption loyalty,

August: Osage County,

children,

Daddy,

daughter,

family,

father,

guilt,

husband,

love,

Puerto Rican,

race

09 March 2014

What’s in a name?

This video really spoke to me via Upworthy:

I recalled my father’s early days in Tennessee. “Enrique” was hard to say, so he always told people to just call him “Jim.” So, all the newspaper clips read “Jim Gonzalez.”

I recalled my father’s early days in Tennessee. “Enrique” was hard to say, so he always told people to just call him “Jim.” So, all the newspaper clips read “Jim Gonzalez.”

This video got me thinking, and of course, when I think, I tweet:

The changing of names. #Whiteout. My dad went from “Enrique” to “Jim.” HT @RococoCocoa

http://t.co/7DOmHonRm4 #American

— mothermade (@mothermade) March 8, 2014

Always mispronounced my name. “Roserita” “Rosalita” “Rosetta” It’s hard to #Whiteout a Puerto Rican name. #adoption

— mothermade (@mothermade) March 8, 2014

BTW, it’s Rosita … and no you can’t call me “Rosie.” #Whiteout

— mothermade (@mothermade) March 8, 2014

My tweets feed into the Facebook account which I maintain for my friends and not the general public. The last tweet brought a flurry of conversation. Unfortunately, not everyone had read the entire thread.

Commenters tried to console me by letting me know that they too suffered from the name shortening. When I tried to explain the entire thread, a commenter asked this question: “Is everything about race to you?”

I responded this way:

“Race is a huge part of me. Not just my Korean self but my Puerto Rican self too. I don’t expect you to know that, but I do expect you to try and understand that. Again, I have been called ‘Roserita, Rosalita, Risotto …’ then, when I correct them, I have been asked, ‘Can I just call you “Rosie”?’ I hate shortened names for that very reason. My children’s names were chosen to be short so they couldn’t be butchered. (But alas, they have been shortened even further.) I get that people like to shorten names often as a expression of familiarity, but that hasn’t always been the case for me. I have had new acquaintances ask to call me ‘Rosie’ and I have accepted that politely … ”

The conversation continued both on my Facebook page and in messenger. The commenter continued that my full Puerto Rican name was as “American” as his. I responded that this is very dependent on what our definition of “American” is. I explained that, to me, the melting pot was a middle class fallacy.

I doubt my commenter understands that I am profiled and assumed by many just on the basis of my name. This commenter’s name is as generic as John Doe. It is difficult for me to explain my experience to someone who has never experienced what I have. My British husband realized this early in our relationship. When we lived in Tennessee and began our hunt for a new apartment to share, I would call and leave a message about a place leaving my name. No one called me back. Then, he would call the same number, and he would immediately get a call back.

If you have followed me for some time, you know how idyllic my life was in Virginia. I had two very dear Asian friends, my kids had friends who resembled them racially. Our community was less segregated, and I was blissful in my everyday life, but there were hints of a longing for an identity. This commenter met me during this time in my life. I was the model minority. Married to a white man, living in a middle class home and going about my daily life as a mother … that was how I was living. I wasn’t questioning the injustices that most likely happened all around me. I was white by default … having a white mother, a white family and white friends.

The commenter’s final words were these: “… it does concern me that you’re so obsessed with race; I think this obsession is a self-defeating waste of energy.” He’s confused. Trust me, I’m still confused, but clarity is coming. My children are the catalysts for change, that is why I spend my time and energy writing about race and adoption.

It seems the further I distance myself from my white identity, the more I am called, “angry.” As long as I stay silent about the prejudices I feel and experience, the less threatened others feel. But why should they feel threatened? I am not angry, but frustrated and motivated to change how we are viewed.

I cope with my racial identity, adopted children cope, my children cope. But why should we just cope? I want to see our communities recognize and address racial inequities instead of saying “It’s better.” I think it is time for those in places of power to cope with the realities of race.

As my fifth grade teacher taught me, “Good, Better, Best … never let it rest, ’til the good is better, and the better is BEST.”

Labels:

American,

angry,

Daddy,

define,

discrimination,

father,

identity,

language,

model minority,

name,

Puerto Rican,

Puerto Rico,

racism,

Upworthy,

white

02 March 2014

What sucks about being adopted?

Here I go, down to the depths.

But before I take you there, I want to tell you that it isn’t that I am unhappy with my adoptive family. I am not angry at them or as some might say, “ungrateful.” Far from it. You can read about my mother, my father, my sister and my extended adoptive family in past blogs to understand the extent of our love.

Now, I want to tell you what sucks about being adopted.

But before I take you there, I want to tell you that it isn’t that I am unhappy with my adoptive family. I am not angry at them or as some might say, “ungrateful.” Far from it. You can read about my mother, my father, my sister and my extended adoptive family in past blogs to understand the extent of our love.

Now, I want to tell you what sucks about being adopted.

- I have no birth certificate. —This frustrates me to no end. Every time, I needed proof of my birth, I had to dig out my naturalization papers (from age 5) and my adoption papers (from age 13 months). Well, that is not proof of my birth. Neither list my birth family or birthdate. This leads me to number 2.

- I have no true birthdate. — Yes, I have one, but it isn’t my true birthdate. It’s an estimate, a fabricated birthdate based on how I appeared on May, 24, 1968.

- I have no birth story. — This never really bothered me until I had children of my own and realized how elemental it was to celebrate that moment when you take your first breath. I love telling my children’s birth stories, and they love hearing them. It bonds us all as a family because we were there at the creation of our family.

- I have no medical history. — This one is a true pain in my rump. With every move or change of health insurance, we must have that initial first meeting with the new doctor. It goes, “Any history of heart disease?” There, I stop them, “No history, I’m adopted.” This happens for me and my children, because obviously, the mother’s family medical history plays into the children’s health.

- I am not really Korean. — This one is complicated, and I have written about it numerous times. While my dad fed me kimchi, and my mother sewed hanbok sets for me, I really wasn’t exposed to the Korean culture in the way I would have been had I grown up in a Korean household. So, I find it irritating when I am viewed as Korean, spoken to in Korean, asked about my “real” Korean family, asked if I know Tae Kwondo … well, you get the picture.

- Reading or hearing the phrase, “like you’re adopted” (insert snarky, teen voice) — Language. Why must people joke with the word “adopted”? Listen, it isn’t funny, and I don’t appreciate being the butt of a joke. I am #notyourbadword. Adoptees are people with feelings, so refrain from using that word in jokes. Got it?

- Being referred to as an “adopted child/children” — Even as we grow into adults, we are referred to as “children.” This is especially prevalent in the media’s headlines and news stories. Someone please add this to the AP Stylebook!

- Being left out of the adoption conversation — Big one related to number 7. As adult adoptees, this perception of us as children seems to exclude us from the adoption dialogue. The fear that we might say or write words that might hurt adoptive parents is insulting. If an adoptive parent is hurt by the words of an adult adoptee, that parent is a grown up, remember? Adults should have the maturity to take someone else’s words, understand them and learn from them.

Labels:

#notyourbadword,

adopted,

adoptee,

adoption,

AP Stylebook,

baby boxes,

birthday,

children,

Daddy,

father,

Korean,

language,

mother,

sister

25 February 2014

They want to know what race we are.

This morning in the rush of getting ready for school, my girl mentions something as she packs her lunch.

“There have been a few racist jokes at school,” she says.

“About what race?” I ask.

“Mine.”

Before I can respond, my beautifully mature little girl says, “I don’t think they mean to be mean.”

She continued, “I did tell him that it wasn’t nice to Asians, and he said he would stop.”

For me, that isn’t the point, but I don’t want to hurt her as she tries to ease my pain. That my ten-year-old must address these microaggressions in her early stages of identity development is disheartening at first, but also enlightening. She has the unique position of being perceived as white. As I have written, this fact frustrates her.

And so, the topic of race continued at dinner …

“Dad, am I white?” she asks.

“Yes, but you are also Korean and Hispanic,” my husband explains.

“Wait,” interrupts my son, “So, I should be checking the box that says I am ‘Hispanic’?”

“Yes,” says my husband.

“You have Papito and our Puerto Rican family’s influence in your life,” I say.

“Well, that’s a culture, not a race thing for me,” says my son, “That’s confusing.”

“Ain’t it though … ” I concluded in my thickest Southern accent.

My children and I are still working out our identities, and sometimes, they are far ahead of me!

Recently, I applied to a job. As always, the race factor came into play in the application. But this one left me with no option to check. Sometimes, I just don’t have an answer.

“There have been a few racist jokes at school,” she says.

“About what race?” I ask.

“Mine.”

Before I can respond, my beautifully mature little girl says, “I don’t think they mean to be mean.”

She continued, “I did tell him that it wasn’t nice to Asians, and he said he would stop.”

For me, that isn’t the point, but I don’t want to hurt her as she tries to ease my pain. That my ten-year-old must address these microaggressions in her early stages of identity development is disheartening at first, but also enlightening. She has the unique position of being perceived as white. As I have written, this fact frustrates her.

And so, the topic of race continued at dinner …

“Dad, am I white?” she asks.

“Yes, but you are also Korean and Hispanic,” my husband explains.

“Wait,” interrupts my son, “So, I should be checking the box that says I am ‘Hispanic’?”

“Yes,” says my husband.

“You have Papito and our Puerto Rican family’s influence in your life,” I say.

“Well, that’s a culture, not a race thing for me,” says my son, “That’s confusing.”

“Ain’t it though … ” I concluded in my thickest Southern accent.

My children and I are still working out our identities, and sometimes, they are far ahead of me!

Recently, I applied to a job. As always, the race factor came into play in the application. But this one left me with no option to check. Sometimes, I just don’t have an answer.

Labels:

culture,

father,

Hapa,

Hispanic,

job application,

Korean,

microaggression,

parenthood,

Puerto Rican,

race,

racial identity,

racism

29 October 2013

Love that Breaks the Mold

Re-homing and litigations have flooded the media stream. I have watched these stories repeat the anger and anguish in the Lost Daughters sisterhood. This frustration and repeated hurt weighed heavily on me.

We honored the legacy of our mother, in my separate photography project, Portrait of a Feminist.

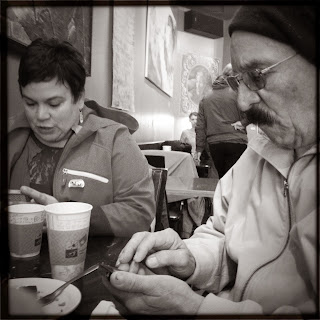

Just as I felt I could take it no more, my family flew into town! All those negative feelings fell away from me when I saw my father, my sister and my niece.

It was a euphoric weekend. Words cannot express what my photographs can. It was a joyous time, filled with laughter and love. My father can be so infectiously funny; he brings out the comedian in my son too.

My daughter told me she heard my sister’s “Mommy voice” but that my sister’s voice was more “thoughtful.” We were told by my children and my niece that the events on Sunday would not include us! Little did they know, we were thrilled by this declaration, though we didn’t show our delight.

But my sister and I were able to spend time with our father and each other.

We honored the legacy of our mother, in my separate photography project, Portrait of a Feminist.

And while I never was able to photograph my mother’s hands, my memory served me well when I saw my sister’s hands. Hers resembled those hands I remembered … the ones that comforted me, embraced me and held me throughout my life.

Many may ask if this biological resemblance might make me long to have the same. I do not. They might ask if I am saddened that I do not share this physical similarity. I am not. My family is that … my family. Their love sustains me, just as it continues to do for my children.

Those who know us see the love that broke the mold. Even those unfamiliar with us see it. This Monday, I took my niece to my daughter’s school so that she could see my daughter. A teacher politely said, “I didn’t know you had another child.”

I replied, “Oh, I don’t. This is my niece.”

“Oh! I thought she was yours since she looks just like your daughter!”

Other friends, upon seeing the photographs of our daughters, wrote things like, “Looking at 2 mini-me’s!”

We just chuckle, because we know that biologically, our girls are not similar. We love the assumption though!

07 August 2013

A Tale of Two Families

Our circle trip began late this July. We were on a mission, two families in ten days … my family in Tennessee, and my husband’s in Canada.

The trip began gleefully with a music mix from my friend, Amy. The first day of driving was shortened by a stay at an Indiana horse ranch. After a couple of nights and a trail ride, we were back on the road to Tennessee.

At first, I had extreme hesitation. While I love my family, I do not love the closed minds and prejudices in Tennessee. We began with the stark contrast of Adult World and the huge cross along the interstate.

The anxiety began to creep in and cover me just as the kudzu drapes and kills the trees in Tennessee. Racist memories from my childhood flooded my mind. I took deep breaths so as not to alarm my kids. Since having children, I worry about their well being, and more specifically, their racial identities.

The conversation in the car began.

“Who are we seeing in Tennessee? Are we going to Papito’s house (my father)?” the kids asked.

“We are not going to Papito’s house. We’ll be staying in Knoxville, where your dad and I met. And you will be meeting your Puerto Rican cousins today,” I answered.

“When are we going to Canada? How long do we have to stay in Tennessee?” the kids continued.

“We will be in Tennessee for a few days, and then we will meet up with your cousins in Canada,” my husband answered.

The conversation then moved on to my husband’s family. Canada is home to his aunt. She and her husband own a lake cottage where we had planned to meet my in-laws for their 50th wedding celebration; however, due to my father-in-law’s recent health decline, my husband’s sister and her family would be the only Brits coming to the party. The kids asked about their relatives across the pond. They all talked happily about similarities. My husband spoke of how our daughter reminded him of his sister at her age. Other biological family traits were bestowed on the kids, and they beamed.

I felt myself receding. My kids weren’t interested in seeing my Puerto Rican family as much as they wanted to see my husband’s. Granted, we haven’t seen my Puerto Rican family in more than five years. Plus, there is the language barrier. But I must admit, I felt slighted. My son does not identify with his Puerto Rican family, but my daughter does. I want desperately for my children to feel the love that I have felt from my family.

The Puerto Ricans, also known as the “Gonzos,” are my family. When someone asks me where I would like to live, I say Puerto Rico. With this side of my family, I feel sudden comfort and security. The Gonzos talk about my son’s resemblance to our great-grandfather. The Gonzos kiss and hug and dance. Boy, do they dance.

We met my father and my cousins, Missiel and Kike, in Tennessee and went to Dollywood. Missiel and I reminisced about their childhood visits to Tennessee and teased Kike. I learned my Spanish pronunciation from my cousins in our backyard. My children stood on the periphery. Missiel and Kike have two children each. Kike’s daughter followed my daughter and wanted to bond with her.

The boys played a little at first.

While things were going well, most times, my kids still clung to one another.

Then, we found the perfect ride to unite all children … against the grown-ups.

As the boys played and joked, Missiel leaned over to me and said, “Noah is a Gonzo! He and Andreas have the same motions!” All the tension and anxiety within me suddenly slid off, and I felt just as I always have when I am with my family … loved.

The trip began gleefully with a music mix from my friend, Amy. The first day of driving was shortened by a stay at an Indiana horse ranch. After a couple of nights and a trail ride, we were back on the road to Tennessee.

At first, I had extreme hesitation. While I love my family, I do not love the closed minds and prejudices in Tennessee. We began with the stark contrast of Adult World and the huge cross along the interstate.

The anxiety began to creep in and cover me just as the kudzu drapes and kills the trees in Tennessee. Racist memories from my childhood flooded my mind. I took deep breaths so as not to alarm my kids. Since having children, I worry about their well being, and more specifically, their racial identities.

The conversation in the car began.

“Who are we seeing in Tennessee? Are we going to Papito’s house (my father)?” the kids asked.

“We are not going to Papito’s house. We’ll be staying in Knoxville, where your dad and I met. And you will be meeting your Puerto Rican cousins today,” I answered.

“When are we going to Canada? How long do we have to stay in Tennessee?” the kids continued.

“We will be in Tennessee for a few days, and then we will meet up with your cousins in Canada,” my husband answered.

The conversation then moved on to my husband’s family. Canada is home to his aunt. She and her husband own a lake cottage where we had planned to meet my in-laws for their 50th wedding celebration; however, due to my father-in-law’s recent health decline, my husband’s sister and her family would be the only Brits coming to the party. The kids asked about their relatives across the pond. They all talked happily about similarities. My husband spoke of how our daughter reminded him of his sister at her age. Other biological family traits were bestowed on the kids, and they beamed.

I felt myself receding. My kids weren’t interested in seeing my Puerto Rican family as much as they wanted to see my husband’s. Granted, we haven’t seen my Puerto Rican family in more than five years. Plus, there is the language barrier. But I must admit, I felt slighted. My son does not identify with his Puerto Rican family, but my daughter does. I want desperately for my children to feel the love that I have felt from my family.

The Puerto Ricans, also known as the “Gonzos,” are my family. When someone asks me where I would like to live, I say Puerto Rico. With this side of my family, I feel sudden comfort and security. The Gonzos talk about my son’s resemblance to our great-grandfather. The Gonzos kiss and hug and dance. Boy, do they dance.

We met my father and my cousins, Missiel and Kike, in Tennessee and went to Dollywood. Missiel and I reminisced about their childhood visits to Tennessee and teased Kike. I learned my Spanish pronunciation from my cousins in our backyard. My children stood on the periphery. Missiel and Kike have two children each. Kike’s daughter followed my daughter and wanted to bond with her.

The boys played a little at first.

And my father encouraged more play together as they all sifted for treasure.

While things were going well, most times, my kids still clung to one another.

Then, we found the perfect ride to unite all children … against the grown-ups.

As the boys played and joked, Missiel leaned over to me and said, “Noah is a Gonzo! He and Andreas have the same motions!” All the tension and anxiety within me suddenly slid off, and I felt just as I always have when I am with my family … loved.

Labels:

British,

Canada,

Daddy,

family history,

father,

Gonzos,

love,

Puerto Rico,

racial identity,

racism,

Tennessee

07 July 2013

The joy of Daddy never leaves you.

I remember the pain of missing my father. He was in Vietnam at the time of my third birthday.

My mother would send audio tapes to him of me saying “Daddy, Daddy, Daddy!” So hearing these children say “Daddy” made me sob uncontrollably.

My dad has such a love for this country. He served 20 years and became a Master Sergeant in the Army. His tracks alone covered Korea, Alaska, Vietnam and Germany. My mother, sister and I moved to Georgia, Kansas and Oklahoma with him where we would wait for him to return to us.

Those days are gone, but the pain of his absence still resides in me. While there are no videos of our reunions, I remember the joy of seeing my Daddy.

05 February 2013

Mi Papi

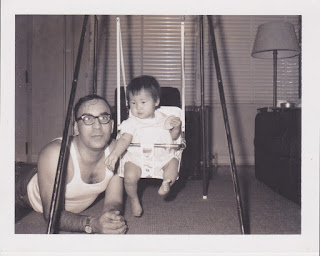

My name reminds me of my heritage. There are palms and beaches. I hear the constant beat of the rhythm of the island. Adobo Pollochon fills my kitchen with smells from my childhood. I am Puertorriqueña. It all began in August of 1968.

Of course he had to cuddle me and our dog. She wasn’t going to be replaced by this new walking being.

I will forever be Daddy’s Girl.

Prompted by my introduction letter, my father, recovering from surgery, took early medical leave to fly to Korea to meet me. He would forever wear a long scar, one that started small but stretched upon carrying all the bags for the trip.

Our meeting included several days of me becoming accustom to my parents. I think I was pretty comfortable.

I was instantly “Daddy’s Girl.” I followed my father wherever he went. I was his shadow.

His time in Korea, at the end of the Korean War, helped him acquire a taste for Korean food. When we are together, he often asks if there’s a Korean restaurant, and when he visits our favorite Korean restaurant in Knoxville, Tennessee, he texts me to let me know. He cannot have his kimchi without thinking of me.

Tucked away, I have his 1950s Korean/English dictionary. He tried to teach me Korean greetings, but I was more interested in the fun Spanish rhymes he would say.

Of course he had to cuddle me and our dog. She wasn’t going to be replaced by this new walking being.

I was introduced at the age of two to my Puerto Rican relatives. The island welcomed me, and I met mi Abuelita, mi Bisabuelita Ita and mi tio y las titis. The smells of the island kitchens still infiltrate my Wisconsin kitchen … especially in the cold months when I need the comfort of arroz y tostones.

My father’s family has committed the same unconditional love that forgets my biological race. In 2000, I brought my infant son to Puerto Rico to introduce him to the island, a land of abrazos y besos. My cousin, Richie, took us to the City Hall of Guayama and found my great grandfather’s portrait. He was the first Enrique. Richie proudly held my son against the portrait and proclaimed that my son looked just like his great-great grandfather, a former mayor of the town.

Quite a resemblance? ¿Verdad?

Enrique … that name has been passed on to every male in the family, but I broke the tradition. My stubborn will missed the subtle cues from my father in phrases like “What do you think about ‘Enrique’ or ‘Fernando’?” I realized my mistake when all the relatives asked how I came to my son’s name. Luckily, I have gotten some redemption now that my son is taking Spanish in school and has taken on the name “Enrique” for his class.

I speak of my mother often since I cannot see or speak with her, but my father is a constant presence in my life. I feel blessed for every day I have him to cuddle my children.

They are proud to have their Latino names and their Papito. They laugh when he uses his fart machine, they enjoy fishing with him as I did, and they admire his oil painting skills.

I am often reminded of the old audio reels from my father’s years in Vietnam. We were separated. I

turned three in Tennessee, but I missed him. I cannot imagine now the

pain my mother felt being so far away from her husband, or his pain at

leaving us and not knowing if he would return. He tells me that he would

often listen to the reel of me saying over and over, “Daddy, Daddy, Daddy! I want my daddy!”

He returned safely to later share one of the most treasured days of my adulthood.

Labels:

Abuelita,

Adobo Pollochon,

arroz y tostones,

Bisabuelita,

Daddy,

Daddy's Girl,

Enrique,

father,

Guayama,

kimchee,

kimchi,

Knoxville,

Korea,

Korean restaurant,

Puerto Rican,

tio,

titi,

unconditional love

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)