Showing posts with label family. Show all posts

Showing posts with label family. Show all posts

16 April 2020

24 November 2017

What is a family?

The question of family comes up not only for National Adoption Month, but also at this time of year when turkeys are basted.

Before my adoptive parents passed away, the Thanksgiving Holiday was my favorite. It meant we would gather in the homes of my East Tennessee relatives. We would feast and gossip, sleep and eat again.

The womenfolk would gather in the kitchen, as the men gathered in front of the tube to watch the game. The house was warm and alive.

Today, my heart is filled with sorrow at the sweetness of those days. I am very thankful for those moments, but not because my Tennerican family “saved” me from a “life of poverty” as the adoption agencies and lawyers would have you believe during their month of November.

I own these memories of home and love, but that does not diminish the importance of my life before them. It only enriches my lived experience.

The connection with my home country has granted me a grace I never consciously knew until my feet landed there. I have reclaimed the Korean BBQ feast, the Korean Spa experience and Noreabang. Those beloved experiences were shared with my closest friends for my fiftieth this year. Those from my pre-Korea days were able to embrace the life I so long for now.

I cherish the quiet November table where my home is filled with the smells of roast parsnips and a chargrilled turkey. There is gratitude for the table set for four and the four cats that stalk the table. Our family tradition is what it is … our tiny family in the midwest. That’s perfect for now.

Before my adoptive parents passed away, the Thanksgiving Holiday was my favorite. It meant we would gather in the homes of my East Tennessee relatives. We would feast and gossip, sleep and eat again.

The womenfolk would gather in the kitchen, as the men gathered in front of the tube to watch the game. The house was warm and alive.

Today, my heart is filled with sorrow at the sweetness of those days. I am very thankful for those moments, but not because my Tennerican family “saved” me from a “life of poverty” as the adoption agencies and lawyers would have you believe during their month of November.

I own these memories of home and love, but that does not diminish the importance of my life before them. It only enriches my lived experience.

The connection with my home country has granted me a grace I never consciously knew until my feet landed there. I have reclaimed the Korean BBQ feast, the Korean Spa experience and Noreabang. Those beloved experiences were shared with my closest friends for my fiftieth this year. Those from my pre-Korea days were able to embrace the life I so long for now.

I cherish the quiet November table where my home is filled with the smells of roast parsnips and a chargrilled turkey. There is gratitude for the table set for four and the four cats that stalk the table. Our family tradition is what it is … our tiny family in the midwest. That’s perfect for now.

Labels:

#NAM,

adoption,

Daddy,

family,

grace,

grateful,

gratitude,

Korea,

Korean BBQ,

Korean Spa,

mom,

National Adoption Month,

Noreabang,

November,

Thanksgiving

16 July 2017

Unmoored

A week ago, I collected lots of Puerto Rican music to remind me of my father.

His loss permeates my soul. He was my anchor in much of my life as a person of color. His love and caring sustained me in my darkest moments … because he understood my sorrows. He gently told me his stories of discrimination and then brushed them off. That is how he survived, and I learned to do the same.

Since his death, I feel so very lost. I need him now. His love surrounded me when I struggled with my role as a mother. He reminded me how very proud he was of me. As much as anyone else said it, I needed him or my mother to say it. As an adoptee, the love and approval from our elders is everything. In most cases, the only people who fill that space are our adoptive parents.

I have searched for the other parents … my original family and my foster family. They hold the key to many of my beginnings. They are unknowns in the crowded subway system in Seoul. In Seoul, I felt their presence in the biological resemblance that surrounded me.

In Wisconsin, I am left to create a space of safety and love. That is our home. So, a few days ago, as I listened to salsa music and did my cleaning, my daughter stopped me to take my picture in the old way … with a Polaroid camera.

There he was. My father was dancing with me as a light. I posted it, and some explained that it must have been a light somewhere or that the camera had something on the lens. But no other photograph she took that night had the same light.

Self-doubt is a terrible thing. But it sank in … the idea that there was a perfectly good explanation for the light.

Then, one of my favorite authors, Sherman Alexie, released a letter about his own loss and his encounters with his late mother. Well, now, I know my father is with me still, and we salsa through the house at all hours!

His loss permeates my soul. He was my anchor in much of my life as a person of color. His love and caring sustained me in my darkest moments … because he understood my sorrows. He gently told me his stories of discrimination and then brushed them off. That is how he survived, and I learned to do the same.

Since his death, I feel so very lost. I need him now. His love surrounded me when I struggled with my role as a mother. He reminded me how very proud he was of me. As much as anyone else said it, I needed him or my mother to say it. As an adoptee, the love and approval from our elders is everything. In most cases, the only people who fill that space are our adoptive parents.

I have searched for the other parents … my original family and my foster family. They hold the key to many of my beginnings. They are unknowns in the crowded subway system in Seoul. In Seoul, I felt their presence in the biological resemblance that surrounded me.

In Wisconsin, I am left to create a space of safety and love. That is our home. So, a few days ago, as I listened to salsa music and did my cleaning, my daughter stopped me to take my picture in the old way … with a Polaroid camera.

There he was. My father was dancing with me as a light. I posted it, and some explained that it must have been a light somewhere or that the camera had something on the lens. But no other photograph she took that night had the same light.

Self-doubt is a terrible thing. But it sank in … the idea that there was a perfectly good explanation for the light.

Then, one of my favorite authors, Sherman Alexie, released a letter about his own loss and his encounters with his late mother. Well, now, I know my father is with me still, and we salsa through the house at all hours!

Labels:

adoption,

adoption agency,

biological parents,

Daddy,

family,

foster family,

Korean,

loss,

mom,

search,

Seoul,

Sherman Alexie

25 December 2016

Twinkie Chronicles: I gather family wherever I can.

Christmas Day is not the holiday I fondly remember. No more does my father’s Spanish-sprinkled “Ho, ho, ho! O’ Christmas Tree, O’ Christmas Treeeeeeee!” ring out over FaceTime. It’s quite silent here now.

This is the first Christmas in my home without my father’s infectious laugh and his many unnecessary packages.

My father was a work-a-holic. He loved his job as, first, an ER nurse, then as a nursing supervisor. His co-workers were the family with whom he spent his holidays. He always worked Christmas. I would beg him to take a holiday off and spend it with us when we were closer; he did so only once after retiring briefly. (He returned to work shortly thereafter.)

That last Christmas, he gave his co-workers all flashlights, his trademark gift. My sister and I, plus our kids and spouses, always received new flashlights. On New Year’s Day, we FaceTimed, and he told me how tired he was. I, again, asked him to take it easy and rest. He told me his time on the Earth was shortening. Daughter deafness overcame me. I told him not to talk about death and that he would be around a long time, just like his mother. That was the last conversation I had with him.

This summer, I decided to try working for national retail companies.

Since moving to the midwest seven years ago, I was finally able to secure a job. For seven years, this white liberal town was closed to me, a woman with a Latina name and professional roots in the South. My years of working as a college professor and a graphic designer meant nothing.

My curriculum vitae would be looked over and tossed aside. Few letters of rejection arrived. The occasional form email might come, and when I responded asking for frankness in what I lacked, I was met with the “we had so many qualified applicants.” I had two interviews in the seven years of my searching.

One year, I would receive an email asking me to set up an interview time with a local technical college. I had submitted my CV in response to a call in the Chronicle of Higher Learning. This was exciting! When I responded with my preferred times, an email quickly responded …

I would bounce back and cause a stir on a national level. The national community would look to me for my words as an adoptee, but once again there would be no reimbursement. My adoptee voice was useful … but not enough to cut a check.

After a soul-searching, extended time in Seoul, I went underground, still talking but now, wounded by my life in the United States … past, present and future. It was time to be compensated for my work.

This holiday season, I worked on Christmas Eve. It was busy and stress-filled. But through all this, I found a new family in my co-workers. As an adoptee, I have learned to find family where I can, but I am reminded of my father’s love for his work “family.” I recall that he, too, was far from his childhood memories in Puerto Rico.

My soul swims in sorrow on the holidays. There is a silence in my home without the voices from my childhood. There are no more cards or calls from Mama and Papito. They are no longer here.

I reflect on two people who gave all they had to leave me joyful memories. From here, I pass my father’s joy and spirit to those at work who have welcomed me with hugs and jests. They filled my days this year with the joy I have been seeking for quite some time now. It is nice to finally have found a home with them.

Happy Holidays.

This is the first Christmas in my home without my father’s infectious laugh and his many unnecessary packages.

My father was a work-a-holic. He loved his job as, first, an ER nurse, then as a nursing supervisor. His co-workers were the family with whom he spent his holidays. He always worked Christmas. I would beg him to take a holiday off and spend it with us when we were closer; he did so only once after retiring briefly. (He returned to work shortly thereafter.)

That last Christmas, he gave his co-workers all flashlights, his trademark gift. My sister and I, plus our kids and spouses, always received new flashlights. On New Year’s Day, we FaceTimed, and he told me how tired he was. I, again, asked him to take it easy and rest. He told me his time on the Earth was shortening. Daughter deafness overcame me. I told him not to talk about death and that he would be around a long time, just like his mother. That was the last conversation I had with him.

This summer, I decided to try working for national retail companies.

Since moving to the midwest seven years ago, I was finally able to secure a job. For seven years, this white liberal town was closed to me, a woman with a Latina name and professional roots in the South. My years of working as a college professor and a graphic designer meant nothing.

My curriculum vitae would be looked over and tossed aside. Few letters of rejection arrived. The occasional form email might come, and when I responded asking for frankness in what I lacked, I was met with the “we had so many qualified applicants.” I had two interviews in the seven years of my searching.

One year, I would receive an email asking me to set up an interview time with a local technical college. I had submitted my CV in response to a call in the Chronicle of Higher Learning. This was exciting! When I responded with my preferred times, an email quickly responded …

“… This is difficult. I’ve never had to do something like this before. I accidentally selected your name to send the interview for and it should have been someone else. I selected from a long list and just grabbed the wrong e-mail address. Unfortunately, you were not selected to be interviewed for this position. We had an extremely competitive pool of over 50 very well qualified candidates. Bringing this down to a small number to interview was very difficult.”

I would bounce back and cause a stir on a national level. The national community would look to me for my words as an adoptee, but once again there would be no reimbursement. My adoptee voice was useful … but not enough to cut a check.

This holiday season, I worked on Christmas Eve. It was busy and stress-filled. But through all this, I found a new family in my co-workers. As an adoptee, I have learned to find family where I can, but I am reminded of my father’s love for his work “family.” I recall that he, too, was far from his childhood memories in Puerto Rico.

My soul swims in sorrow on the holidays. There is a silence in my home without the voices from my childhood. There are no more cards or calls from Mama and Papito. They are no longer here.

I reflect on two people who gave all they had to leave me joyful memories. From here, I pass my father’s joy and spirit to those at work who have welcomed me with hugs and jests. They filled my days this year with the joy I have been seeking for quite some time now. It is nice to finally have found a home with them.

Happy Holidays.

Labels:

#flipthescript,

#TwinkieChronicles,

Daddy,

family,

holidays,

retail work,

sorrow

12 November 2016

This is what my silence wrought.

Thirty-four years ago, I was called a swamp rat.

Thirty-four years ago, I was told to get back on the boat.

Thirty-four years ago, my church harbored racists who spoke these words.

And I was silent. I protected my white family from the ugliness.

Twenty-nine years ago, I lay half dressed on a bed.

Twenty-nine years ago, I felt dirty and used.

Twenty-nine years ago, the frat house I thought was a haven held sexual predators.

And I was silent. I protected the white men who I thought loved me like a little sis.

Four years ago, a studio mate told an inappropriate joke.

Four years ago, a studio mate slapped my butt in the empty studio.

Four years ago, the space that I saw as my solace became tainted.

And I was silent. I protected a white man I had thought was a friend.

Two years ago, at a gala, a man sat next to me and my husband.

Two years ago, this white man reached over and touched my cheek with his palm.

Two years ago, a nice evening turned sour.

And we were silent. We decided this white donor was too important to humiliate.

Four months ago, my son walked the two blocks from the bus stop to our home.

Four months ago, my son was stopped in his neighborhood.

Four months ago, a white man walking his dog asked my son what he was doing here.

And he was silent. He walked with his head down and picked up the pace.

Every school day, my son faces bullying.

Every school day, my son hears words like “rice fag.”

Every school day, my son dreads facing these white oppressors alone.

And he is silent.

Now, I am no longer silent. We tried to be good, kind, quiet … the model minority.

We have watched our Black brothers and sisters die in front of our eyes, and we have walked beside them in protest. I hoped a white woman would save us, but white supremacy is stronger than we realized. The hold that racism has on the United States has taken my church, my white adoptive family and the public places we once thought safe.

So for now, we huddle at home. I hold my children close as they call America the land of Jim Crow and The Purge. What else can we do?

Labels:

#BlackLivesMatter,

bullying,

children,

church,

faith,

family,

high school,

model minority,

Poetry,

racism,

sexual assault,

son

09 January 2016

Twinkie Chronicles: The China Doll has Children.

“Ain’t she just the cutest ‘China doll’! You’ns must be mighty proud of her.”

My mother’s face would mangle and turn blood red, no matter who said it. “She’s my daughter, and she’s Korean, not Chinese.”

This was the dialogue when we would return to my mother’s hometown in the 1970s. She actually never wanted to return to that small town but wanted a life in a larger community. My parents had lived in Yokohama, Japan, for three years, and my mother longed to have those days back.

Yet, in 1976, my father, thinking it would be nice for his wife to have her mother nearby, pursued a job in my mother’s hometown. And thusly, my life progressed there, amidst the racism and ignorance of the small-town mentality. It pains me to even type this, as I still have relatives there who I love dearly and would do anything to protect. Their love for me is unconditional, and here, I leave it at that.

After escaping my hometown, I moved to the city that started my parents’ romance … Knoxville. It was bigger and brighter; there was more dialogue, and I relished the “changes” I hoped to see for my home state during the 1992 election.

Much of that optimism fell as I returned pregnant in the late 1990s. My husband and I stayed with a friend that holiday season in Knoxville. During our dinner, my friend’s husband said something that froze me to the core … “You guys will make a beautiful baby. Hybrids are attractive and robust genetically.”

We were shocked. Our marriage and our family planning was never an experiment in procreation. If I had had the words then, WHAT. THE. FUCK.

Our planning did include communities with larger populations of people of color. We wanted our children to not feel the isolation I had as a child. But even the best intentions never prepare you for the reality of racism and race comparisons.

Now that my children are growing taller than me, I find myself gushing over all infants and toddlers. I long for those days. My daughter, the youngest, has a difficult time watching this crazy behavior where I smile at strangers’ children and hold and then sniff our friends’ infants.

Since coming to Korea, her disgust of babies has changed to fear. My daughter now senses my complete connection to the little ones here. Where I see little versions of what I could have been, my daughter sees versions of what she thinks I want.

Difficult to tease out with her, she and I only talk briefly. She talks mostly to her father about her fear that I will remain in Korea and marry a Korean man to have Korean children. She does not see the complexities. All I can do is reassure her.

The worst struggles come when other Korean adoptees gush over her and her brother. They compliment them on how beautiful and handsome they are. And one well-meaning person once said, “I guess I would have to marry a white man to get beautiful children like that.”

Though the person did not realize my daughter was listening (she and her brother tend to keep ear buds in and eyes on screen) her ears were burning. She wanted reassurance that my motives were pure. She wanted reassurance that I loved her father.

I assured her, but I also elaborated on why a Korean adoptee looks at her with such longing.

My mother’s face would mangle and turn blood red, no matter who said it. “She’s my daughter, and she’s Korean, not Chinese.”

This was the dialogue when we would return to my mother’s hometown in the 1970s. She actually never wanted to return to that small town but wanted a life in a larger community. My parents had lived in Yokohama, Japan, for three years, and my mother longed to have those days back.

Yet, in 1976, my father, thinking it would be nice for his wife to have her mother nearby, pursued a job in my mother’s hometown. And thusly, my life progressed there, amidst the racism and ignorance of the small-town mentality. It pains me to even type this, as I still have relatives there who I love dearly and would do anything to protect. Their love for me is unconditional, and here, I leave it at that.

After escaping my hometown, I moved to the city that started my parents’ romance … Knoxville. It was bigger and brighter; there was more dialogue, and I relished the “changes” I hoped to see for my home state during the 1992 election.

Much of that optimism fell as I returned pregnant in the late 1990s. My husband and I stayed with a friend that holiday season in Knoxville. During our dinner, my friend’s husband said something that froze me to the core … “You guys will make a beautiful baby. Hybrids are attractive and robust genetically.”

We were shocked. Our marriage and our family planning was never an experiment in procreation. If I had had the words then, WHAT. THE. FUCK.

Our planning did include communities with larger populations of people of color. We wanted our children to not feel the isolation I had as a child. But even the best intentions never prepare you for the reality of racism and race comparisons.

Now that my children are growing taller than me, I find myself gushing over all infants and toddlers. I long for those days. My daughter, the youngest, has a difficult time watching this crazy behavior where I smile at strangers’ children and hold and then sniff our friends’ infants.

Since coming to Korea, her disgust of babies has changed to fear. My daughter now senses my complete connection to the little ones here. Where I see little versions of what I could have been, my daughter sees versions of what she thinks I want.

Difficult to tease out with her, she and I only talk briefly. She talks mostly to her father about her fear that I will remain in Korea and marry a Korean man to have Korean children. She does not see the complexities. All I can do is reassure her.

The worst struggles come when other Korean adoptees gush over her and her brother. They compliment them on how beautiful and handsome they are. And one well-meaning person once said, “I guess I would have to marry a white man to get beautiful children like that.”

Though the person did not realize my daughter was listening (she and her brother tend to keep ear buds in and eyes on screen) her ears were burning. She wanted reassurance that my motives were pure. She wanted reassurance that I loved her father.

I assured her, but I also elaborated on why a Korean adoptee looks at her with such longing.

“Before you and your brother, I had no other person that shared my appearance, my mannerisms and my genetics. Korean adoptees who have yet to have children of their own are curious. They long to see themselves reflected in another human being. That does not excuse the comment or how it makes you feel. Your father and I love one another, and we love you and your brother. We are a family.”

Labels:

#TwinkieChronicles,

adoptee,

adult adoptee,

babies,

biological child,

children,

China Doll,

family,

genetics,

identity,

Korea,

Korean,

loss,

race,

racism,

Seoul,

white

05 December 2015

Love is enough, until it’s gone.

Blocked from knowing my history, a product of the Baby Box theory, I only remember the love of one family. It wasn’t the choice of my adoptive family (or what I will refer to as “my family” in this post) to keep me from my first family. The members of my family believed for all legal purposes that I was an orphan that became their daughter and sister.

I have very fond memories of my family. As I sit in Seoul, peeling chestnuts and eating them raw, I remember the chestnut orchard of my grandfather. I would hang and swing from the branches of those mighty trees in the fall weather of East Tennessee. It was idyllic and comforting. I loved breaking apart the prickly pods to reveal the raw meat of a nut no one else loved as I did …

In Seoul, I bought a bag of corn chips, much like the Bugles my grandmother bought for me from the vending machine where she cleaned rooms at the local hotel. My family’s life was simple. We lived simply, just as I imagine my first family did. It seems fitting that I would become the daughter of a set of parents who grew up poor as well.

The days of reminiscing with my parents are gone. My mother passed just as I was becoming the mom she had taught me to be. For years, I struggled with the loss of her.

My father and sister stood with me when my mom died. Their grief was mine and mine, theirs. We spoke among ourselves about her impact on our lives. I shared with them the pains of feeling alone in my parenting.

My younger sister would soon have a little one of her own. Feeling comfortable with infants (after having my two), I cherished the time spent with her as she struggled to wrestle motherhood to the ground. One day, she said, “You have done the very thing that would have made Mom so very proud.” That was a golden moment in my life. I was “Mom.”

My younger sister would soon have a little one of her own. Feeling comfortable with infants (after having my two), I cherished the time spent with her as she struggled to wrestle motherhood to the ground. One day, she said, “You have done the very thing that would have made Mom so very proud.” That was a golden moment in my life. I was “Mom.”

My father’s family became the strength in the lives of my children as they grew up only really knowing my father and not my mother. We made many trips to Puerto Rico to connect. They feel they are Puerto Rican.

But our time with my father was also fleeting. His death this last January was a blow we never imagined at the time. He had been my link to Korea … his time there, his love for the country and his honest interest in my original family search. He was my supporter when the world’s eyes saw me as a disloyal adoptee.

In the following months, I would learn more about my father’s time in Korea and his short love affair that resulted in a son … a man only two years older than me and the physical embodiment of the identity I had spent my entire life building.

What I wish adoptive parents would consider is that once they pass on, the adoptee is truly alone. We are left with a family that is only ours by association. In my case, my extended family works to stay connected, but deep down, I feel separate. My children and I long for a connection to the one man who embodies my father and my biological Korean side.

My writing is not for my late parents. My writing addresses me as a person, a mother, an adoptee, my parents’ daughter, my original family’s lost daughter and as the foster child to a foster mother I can only see in faded pictures.

This post was originally published on the Lost Daughters blog for National Adoption Month.

I have very fond memories of my family. As I sit in Seoul, peeling chestnuts and eating them raw, I remember the chestnut orchard of my grandfather. I would hang and swing from the branches of those mighty trees in the fall weather of East Tennessee. It was idyllic and comforting. I loved breaking apart the prickly pods to reveal the raw meat of a nut no one else loved as I did …

In Seoul, I bought a bag of corn chips, much like the Bugles my grandmother bought for me from the vending machine where she cleaned rooms at the local hotel. My family’s life was simple. We lived simply, just as I imagine my first family did. It seems fitting that I would become the daughter of a set of parents who grew up poor as well.

The days of reminiscing with my parents are gone. My mother passed just as I was becoming the mom she had taught me to be. For years, I struggled with the loss of her.

My father and sister stood with me when my mom died. Their grief was mine and mine, theirs. We spoke among ourselves about her impact on our lives. I shared with them the pains of feeling alone in my parenting.

My younger sister would soon have a little one of her own. Feeling comfortable with infants (after having my two), I cherished the time spent with her as she struggled to wrestle motherhood to the ground. One day, she said, “You have done the very thing that would have made Mom so very proud.” That was a golden moment in my life. I was “Mom.”

My younger sister would soon have a little one of her own. Feeling comfortable with infants (after having my two), I cherished the time spent with her as she struggled to wrestle motherhood to the ground. One day, she said, “You have done the very thing that would have made Mom so very proud.” That was a golden moment in my life. I was “Mom.”My father’s family became the strength in the lives of my children as they grew up only really knowing my father and not my mother. We made many trips to Puerto Rico to connect. They feel they are Puerto Rican.

But our time with my father was also fleeting. His death this last January was a blow we never imagined at the time. He had been my link to Korea … his time there, his love for the country and his honest interest in my original family search. He was my supporter when the world’s eyes saw me as a disloyal adoptee.

In the following months, I would learn more about my father’s time in Korea and his short love affair that resulted in a son … a man only two years older than me and the physical embodiment of the identity I had spent my entire life building.

What I wish adoptive parents would consider is that once they pass on, the adoptee is truly alone. We are left with a family that is only ours by association. In my case, my extended family works to stay connected, but deep down, I feel separate. My children and I long for a connection to the one man who embodies my father and my biological Korean side.

My writing is not for my late parents. My writing addresses me as a person, a mother, an adoptee, my parents’ daughter, my original family’s lost daughter and as the foster child to a foster mother I can only see in faded pictures.

This post was originally published on the Lost Daughters blog for National Adoption Month.

Labels:

adoptive parents,

brother,

Daddy,

family,

loss,

mom,

motherhood,

Puerto Rico,

sister,

sorrow

11 November 2015

Korea: Marriage, White Privilege and Bullies

Marriage is hard. It’s exhilarating at first; then the relationship slides into routine. Add children, and it shifts from the couple to the kids.

As an adoptee, this is bliss until the moment you realize you have some deep-seeded racial identity issues. It isn’t that I didn’t know I had them, I knew I wanted to be white. But I never felt strong enough to speak for myself, so I stayed silent, dated only white guys and you know the rest of that story.

The strength in our marriage is that we are able to adapt and learn. Sometimes, the learning is hard for both of us, as we learn that we are the two extremes that play out in our children. Many times, I get frustrated and angry without explaining why. That is truly tough on my husband.

Monday, he took the day off so that we could take a much needed family break at Lotte World Adventure, “the largest indoor amusement park in the world.” There was joy and excitement. We were taking selfies and “wrecking noobs.”

No one spoke English, and we often wandered around not really knowing what to do. Of course, as usual, when we tried speaking or ordering, the cashier would always look to me and talk to me in Korean. Then, my sheepish voice would reveal that I was an American. That’s a running theme here … Korean women speaking for the family as a whole. But my voice is again silenced in that role.

My husband can speak English, and Koreans rush to help him and find translation. Or they just throw up their hands and make a face.

Two distinct things happened to us that day. We learned about white privilege in Korea, and how it isn’t the same as just plain bullying.

The first incident happened as we waited to give one another whiplash on the bumper cars. As we inched up to the front of the line, the ticket woman asked us how many we had in our party. My husband held up his four fingers. She counted and allowed the two women behind me to enter and take the last two remaining cars. This, of course, sparked our families competitive side.

We watched for the fastest, most responsive cars and yelled out to one another what car we were eyeing. It was sheer family fun! As the last group cleared the track, my husband, son and daughter began to rush toward the cars, but the ticket taker stopped me at the gate and asked for my ticket. She hadn’t asked my husband for his ticket, and my ticket was in my husband’s pocket.

I called his name once, louder a second time and then I shouted his name in panic the third time, telling him I needed my ticket. He was trying to seat himself in his car, so he was a bit perturbed that I had yelled at him. He showed my ticket, and I was allowed to enter the arena.

My head was spinning. “Hadn’t she just a few minutes before counted us as a party of four? And why would she separate me from my family?” I felt stupid and less than. Once we got off the ride, my daughter sulked saying she was embarrassed by what had happened … Mom yelled and Dad was visibly irritated.

I apologized, and we moved on to our next adventure. But as we waited again for the next ride, we had the same thing happen. This ride took families, so we were once again counted. When my husband gave the young woman our four tickets, she questioned where the fourth person was, and my husband had to point out that I was his wife.

There are many things I have tried to rationalize … “maybe the Korean women hold the tickets, maybe my kids look more like my husband and less like me, maybe I just do not look like I belong in my family.”

As we took off in our fake hot air balloon, I let my family know how I was feeling. This second time, they came to the realization that I was indeed not seen as part of our family. I was othered, and it stung just as it always does.

In the old days, when I spoke to adoptive parents and social workers, I advised them to make sure they had put themselves in a situation where they were the minority. But that day, I realized that even if a white person is the minority, he or she still holds white privilege and is afforded things based on that role in our world.

When my husband and I lived in Rwanda, we were in the minority, but he was viewed as superior, and I was inappropriately touched and questioned by teenage soldiers. As a Korean woman, I feel less than no matter where I am. Most times, I am a lone Asian woman, so there are no allies. In my aloneness, I am quiet and try to blend into the background.

Having said this, I want to tell you what happened next. Our last ride was a Magic Pass ride, so we we were able to miss some of the queuing. Once we got to the final part of the line, I noticed two teen boys behind us staring at my son and making rude gestures about him. They were looking at my son, making faces and laughing. When I realized what was happening, I began to stare at them with disdain. They noticed my stare and began to hide behind others in line between us.

Feeling that I had stopped it before my son noticed, I moved my gaze to the front of the line. Here I witnessed a group of eight teenage boys. The most attractive one wore a white shirt and a Kpop hairdo. He was making fun of my husband’s nose. Using his hands, he acted as though he had a large nose and made odd gestures with his eyes too. The other seven laughed and looked back at my family.

Again, I stared at them, showing my disgust. They, too, looked away and hid. They would quickly glance to see if I was still there, and my laser gaze met theirs. I wanted them to feel ashamed and scorned. I whispered to my husband that this was happening so that he could stare at the eight in front of us, and I could stare at the two behind.

Once that ride was over, so was I. We left Lotte World and moved to our favorite restaurant. We arrived to the cheerful staff who always serve us. They were chatty and friendly. Dinner time is our family time to discuss our day. My husband opened with discussion about the eight boys. He asked me if I wanted to tell the story.

But I began with the story of the two boys. My husband asked why I started with that story, but I felt our son needed to know he was being targeted as much as he needed to know that his father was targeted too. You see, in my mind, these were not instances of racism against my husband as a white man, but instances of bullying. The boys would make fun of anything different, and it wasn’t based on a power structure.

My kids understand so much already about racism and bullies, it seems fair they know the full story. They see their parents disagree, discuss and assess together. It isn’t always pretty, but they know we love one another and that disagreements are not cause for divorce in our family. There is respect. While it may take us time to fully understand, we work to see the other’s side.

We have a few more months here in Korea. I doubt this will be the last day we will need to detox, but boy, was it a doozy.

As an adoptee, this is bliss until the moment you realize you have some deep-seeded racial identity issues. It isn’t that I didn’t know I had them, I knew I wanted to be white. But I never felt strong enough to speak for myself, so I stayed silent, dated only white guys and you know the rest of that story.

The strength in our marriage is that we are able to adapt and learn. Sometimes, the learning is hard for both of us, as we learn that we are the two extremes that play out in our children. Many times, I get frustrated and angry without explaining why. That is truly tough on my husband.

Monday, he took the day off so that we could take a much needed family break at Lotte World Adventure, “the largest indoor amusement park in the world.” There was joy and excitement. We were taking selfies and “wrecking noobs.”

No one spoke English, and we often wandered around not really knowing what to do. Of course, as usual, when we tried speaking or ordering, the cashier would always look to me and talk to me in Korean. Then, my sheepish voice would reveal that I was an American. That’s a running theme here … Korean women speaking for the family as a whole. But my voice is again silenced in that role.

My husband can speak English, and Koreans rush to help him and find translation. Or they just throw up their hands and make a face.

Two distinct things happened to us that day. We learned about white privilege in Korea, and how it isn’t the same as just plain bullying.

The first incident happened as we waited to give one another whiplash on the bumper cars. As we inched up to the front of the line, the ticket woman asked us how many we had in our party. My husband held up his four fingers. She counted and allowed the two women behind me to enter and take the last two remaining cars. This, of course, sparked our families competitive side.

We watched for the fastest, most responsive cars and yelled out to one another what car we were eyeing. It was sheer family fun! As the last group cleared the track, my husband, son and daughter began to rush toward the cars, but the ticket taker stopped me at the gate and asked for my ticket. She hadn’t asked my husband for his ticket, and my ticket was in my husband’s pocket.

I called his name once, louder a second time and then I shouted his name in panic the third time, telling him I needed my ticket. He was trying to seat himself in his car, so he was a bit perturbed that I had yelled at him. He showed my ticket, and I was allowed to enter the arena.

My head was spinning. “Hadn’t she just a few minutes before counted us as a party of four? And why would she separate me from my family?” I felt stupid and less than. Once we got off the ride, my daughter sulked saying she was embarrassed by what had happened … Mom yelled and Dad was visibly irritated.

I apologized, and we moved on to our next adventure. But as we waited again for the next ride, we had the same thing happen. This ride took families, so we were once again counted. When my husband gave the young woman our four tickets, she questioned where the fourth person was, and my husband had to point out that I was his wife.

There are many things I have tried to rationalize … “maybe the Korean women hold the tickets, maybe my kids look more like my husband and less like me, maybe I just do not look like I belong in my family.”

As we took off in our fake hot air balloon, I let my family know how I was feeling. This second time, they came to the realization that I was indeed not seen as part of our family. I was othered, and it stung just as it always does.

In the old days, when I spoke to adoptive parents and social workers, I advised them to make sure they had put themselves in a situation where they were the minority. But that day, I realized that even if a white person is the minority, he or she still holds white privilege and is afforded things based on that role in our world.

When my husband and I lived in Rwanda, we were in the minority, but he was viewed as superior, and I was inappropriately touched and questioned by teenage soldiers. As a Korean woman, I feel less than no matter where I am. Most times, I am a lone Asian woman, so there are no allies. In my aloneness, I am quiet and try to blend into the background.

Having said this, I want to tell you what happened next. Our last ride was a Magic Pass ride, so we we were able to miss some of the queuing. Once we got to the final part of the line, I noticed two teen boys behind us staring at my son and making rude gestures about him. They were looking at my son, making faces and laughing. When I realized what was happening, I began to stare at them with disdain. They noticed my stare and began to hide behind others in line between us.

Feeling that I had stopped it before my son noticed, I moved my gaze to the front of the line. Here I witnessed a group of eight teenage boys. The most attractive one wore a white shirt and a Kpop hairdo. He was making fun of my husband’s nose. Using his hands, he acted as though he had a large nose and made odd gestures with his eyes too. The other seven laughed and looked back at my family.

Again, I stared at them, showing my disgust. They, too, looked away and hid. They would quickly glance to see if I was still there, and my laser gaze met theirs. I wanted them to feel ashamed and scorned. I whispered to my husband that this was happening so that he could stare at the eight in front of us, and I could stare at the two behind.

Once that ride was over, so was I. We left Lotte World and moved to our favorite restaurant. We arrived to the cheerful staff who always serve us. They were chatty and friendly. Dinner time is our family time to discuss our day. My husband opened with discussion about the eight boys. He asked me if I wanted to tell the story.

But I began with the story of the two boys. My husband asked why I started with that story, but I felt our son needed to know he was being targeted as much as he needed to know that his father was targeted too. You see, in my mind, these were not instances of racism against my husband as a white man, but instances of bullying. The boys would make fun of anything different, and it wasn’t based on a power structure.

My kids understand so much already about racism and bullies, it seems fair they know the full story. They see their parents disagree, discuss and assess together. It isn’t always pretty, but they know we love one another and that disagreements are not cause for divorce in our family. There is respect. While it may take us time to fully understand, we work to see the other’s side.

We have a few more months here in Korea. I doubt this will be the last day we will need to detox, but boy, was it a doozy.

Labels:

bullying,

culture,

discrimination,

family,

husband,

identity,

Korea,

Lotte World,

marriage,

search,

white privilege

27 September 2015

Korea: A Thanksgiving of Another Kind

The market was bustling as my daughter and I sussed out our lunch for Friday. I was especially excited to see the variety of things for sale. It was like nothing I had seen before in the market. My favorite melons in small sizes, peeled chestnuts, Korean pears as big as a size 3 soccer ball and gift packs of Spam.

The expectation of Chuseok was infectious. Women rushing, squeezing and choosing the ingredients to feed the souls of their children. It felt very much like the build-up to Thanksgiving in the days of my youth. (Today, the build-up to Thanksgiving is less than I remember as it seems to be eclipsed by Halloween and December holidays.)

Thanksgiving in those days was my favorite holiday. It meant not only time off, but time to hang with my family and eat really good food. My mother loved it because it was her time to show her stuff. Our little family would gather with my grandmother, and the entire weekend included treks to cousins’ and aunts’ houses for more good food. We would sit around the kitchen table, mostly the women, as the men watched the Tennessee Vols play ball. My husband enjoyed the women’s table. If you left the table to pee, you knew everyone would talk about you. I often would hold it.

Korean Chuseok is very similar as it celebrates the coming together of families. For me, this is bittersweet. My grandmother, my mother and my great aunts are long gone. Thanksgiving for me today, is just my husband, my kids and me. So, it seemed this Chuseok would be more of the same.

On the Eve of Chuseok, I had my Mom’s day off. I wrote for the Lost Daughters, then went to Ehwa Women’s University area. Most shops were beginning to close in my neighborhood of Sinjeong, and the subway seemed skeletal. The tired faces of the elders on the train had my mind racing. Could they be without family too for Chuseok? Were they mourning the loss of a child to adoption? Am I that child?

Yet, when I walked out of the subway station into Ehwa, life presented herself as young women shopped with friends and some shopped with their mothers.

I remembered my days of shopping with my mother during the Thanksgiving holiday and then it hit me … how profoundly alone I felt and how I missed these moments with my family.

I bought dinner from the 7-Eleven, returned to our apartment, peeled a few chestnuts and tried to sleep. Lately, sleep does not come easily, and when I slide down into dream land, my dreams become anxious tales of being back in Wisconsin … empty-handed.

The expectation of Chuseok was infectious. Women rushing, squeezing and choosing the ingredients to feed the souls of their children. It felt very much like the build-up to Thanksgiving in the days of my youth. (Today, the build-up to Thanksgiving is less than I remember as it seems to be eclipsed by Halloween and December holidays.)

Thanksgiving in those days was my favorite holiday. It meant not only time off, but time to hang with my family and eat really good food. My mother loved it because it was her time to show her stuff. Our little family would gather with my grandmother, and the entire weekend included treks to cousins’ and aunts’ houses for more good food. We would sit around the kitchen table, mostly the women, as the men watched the Tennessee Vols play ball. My husband enjoyed the women’s table. If you left the table to pee, you knew everyone would talk about you. I often would hold it.

Korean Chuseok is very similar as it celebrates the coming together of families. For me, this is bittersweet. My grandmother, my mother and my great aunts are long gone. Thanksgiving for me today, is just my husband, my kids and me. So, it seemed this Chuseok would be more of the same.

On the Eve of Chuseok, I had my Mom’s day off. I wrote for the Lost Daughters, then went to Ehwa Women’s University area. Most shops were beginning to close in my neighborhood of Sinjeong, and the subway seemed skeletal. The tired faces of the elders on the train had my mind racing. Could they be without family too for Chuseok? Were they mourning the loss of a child to adoption? Am I that child?

Yet, when I walked out of the subway station into Ehwa, life presented herself as young women shopped with friends and some shopped with their mothers.

I remembered my days of shopping with my mother during the Thanksgiving holiday and then it hit me … how profoundly alone I felt and how I missed these moments with my family.

I bought dinner from the 7-Eleven, returned to our apartment, peeled a few chestnuts and tried to sleep. Lately, sleep does not come easily, and when I slide down into dream land, my dreams become anxious tales of being back in Wisconsin … empty-handed.

I am a tale told like a secret, full of lies and deception, but signifying something. I just cannot figure out what it is. #Seoulsearching— mothermade (@mothermade) September 26, 2015

Chuseok began like any other, but I was looking forward to time at KoRoot. KoRoot supports adoptees when they return to Korea with translations, a guest house and a place to reconnect with other adoptees. I needed this time; this was my homecoming.

As usual, finding it and navigating the day with the family had its little moments of “family drama,” and once we arrived, my kids were ready to leave. I enjoyed reconnecting with Pastor Kim of KoRoot and bringing a copy of Dear Wonderful You to its new home.

Eating really good Korean food healed my soul. Seeing and meeting so many other Korean adoptees again gave me more strength to continue. Many of them had been in Korea for four, five and even fifteen years! Noticing my connection, my husband offered to take the children home to give me time to reconnect.

Once again, the community of adoptees pulls me up. I found my home for now, and homecoming was sweet.

Once again, the community of adoptees pulls me up. I found my home for now, and homecoming was sweet.

11 August 2015

The Birthright

“Nobody’s Perfect.”

This was the line that echoed throughout my childhood. My sister and I had matching nighties with this phrase emblazoned on them. One evening, my three-year-old sibling put hers on backwards. She grinned and said, “Nobody’s Perfect!”

Imperfection runs amok in society, but we try our damnedest to cloak it … mask it … shroud it … bury it.

I was once someone’s secret, the personified shame of some encounter. I am still hidden, but there are now more treasures to be found.

Many times in my life, my father reminded me of the country from which I came. He gave me his 1961 Korean dictionary. He sought out Korean restaurants. He insisted I read books on the post Korean War Comfort Women. The latter always disturbed me. It was as though I had insulted him for dismissing a book I couldn’t stomach at the time.

When my son was seven weeks old, my mother suffered a stroke. This event brought our small family together; my parents had been legally separated for more than 18 years. On our first evening together, my sister, my father, my infant son and I shared a hospital hospitality room.

As a new mother, I couldn’t settle my son down. His infant screams were piercing. We all tried various tricks, but nothing worked. Suddenly, my father shouted, “Can you shut that baby up?!”

My sister quickly whisked my father out the room. The outburst seemed to work, and I was able to eventually calm my child. Sobbing uncontrollably and asking for my forgiveness, my father re-entered the room. I tried to calm him and told him not to worry, that we all were tired and stressed, but he kept insisting that he was a bad man and that my sister and I had no idea what a bad person he was.

This scene always lingered with me. My heart broke for my father. He turned around and cared for my mother until her death some eight months later. She fell in love with him all over again as he made her every meal for the remainder of her life.

Last summer, as I searched for my birth mother, my father called me each morning to check in and see what I had done. He was living vicariously through me as I enjoyed the experience of being Korean in Korea. The day I visited my agency to receive nothing, I begged him to come to Korea with me and help me by asking on my behalf for my file. His response was peculiar … “They didn’t tell me anything either.”

When my father died in January, my heart broke into an infinite number … I felt fully alone in my quest. My most fervent supporter was gone.

Five months later, I discovered the cornerstone, the piece that fit all the others together. My father had been stationed in Korea. In my mind, this fact was the reason why he loved Korea, longed for it and was so determined to keep me Korean. I was his connection to a time that meant a great deal to him.

I unearthed that his connection to Korea went beyond me and my connection. He had a secret too. He fathered a son. Somewhere in Korea or beyond is a Korean Puerto Rican who has my identity as his birthright.

Brother/Uncle, we will soon be in Korea to search for you as well …

This was the line that echoed throughout my childhood. My sister and I had matching nighties with this phrase emblazoned on them. One evening, my three-year-old sibling put hers on backwards. She grinned and said, “Nobody’s Perfect!”

Imperfection runs amok in society, but we try our damnedest to cloak it … mask it … shroud it … bury it.

I was once someone’s secret, the personified shame of some encounter. I am still hidden, but there are now more treasures to be found.

Many times in my life, my father reminded me of the country from which I came. He gave me his 1961 Korean dictionary. He sought out Korean restaurants. He insisted I read books on the post Korean War Comfort Women. The latter always disturbed me. It was as though I had insulted him for dismissing a book I couldn’t stomach at the time.

When my son was seven weeks old, my mother suffered a stroke. This event brought our small family together; my parents had been legally separated for more than 18 years. On our first evening together, my sister, my father, my infant son and I shared a hospital hospitality room.

As a new mother, I couldn’t settle my son down. His infant screams were piercing. We all tried various tricks, but nothing worked. Suddenly, my father shouted, “Can you shut that baby up?!”

My sister quickly whisked my father out the room. The outburst seemed to work, and I was able to eventually calm my child. Sobbing uncontrollably and asking for my forgiveness, my father re-entered the room. I tried to calm him and told him not to worry, that we all were tired and stressed, but he kept insisting that he was a bad man and that my sister and I had no idea what a bad person he was.

This scene always lingered with me. My heart broke for my father. He turned around and cared for my mother until her death some eight months later. She fell in love with him all over again as he made her every meal for the remainder of her life.

Last summer, as I searched for my birth mother, my father called me each morning to check in and see what I had done. He was living vicariously through me as I enjoyed the experience of being Korean in Korea. The day I visited my agency to receive nothing, I begged him to come to Korea with me and help me by asking on my behalf for my file. His response was peculiar … “They didn’t tell me anything either.”

When my father died in January, my heart broke into an infinite number … I felt fully alone in my quest. My most fervent supporter was gone.

Five months later, I discovered the cornerstone, the piece that fit all the others together. My father had been stationed in Korea. In my mind, this fact was the reason why he loved Korea, longed for it and was so determined to keep me Korean. I was his connection to a time that meant a great deal to him.

I unearthed that his connection to Korea went beyond me and my connection. He had a secret too. He fathered a son. Somewhere in Korea or beyond is a Korean Puerto Rican who has my identity as his birthright.

Brother/Uncle, we will soon be in Korea to search for you as well …

Labels:

biological father,

birth father rights,

brother,

Daddy,

family,

genetics,

Korean,

mom,

siblings,

sister

09 November 2014

Let’s hear those adoptee #validvoices #flipthescript! Add yours!

@genevievedoull @RebeccaGHawkes Yes, your opinion is your own. I respect that. It has been a rough day for many of us, working to see better

— mothermade (@mothermade) November 9, 2014

.@iamadopted @BlessEnt Try to focus on the #adoptee posts. APs can speak, but again, it is OUR. TIME. #flipthescript #NAM14

— mothermade (@mothermade) November 9, 2014

Telling one’s truth is exhausting! Adoptees are taking the mic and tweeting. #FliptheScript began at Lost Daughters when I posed a campaign for the month of November. My sisters were supportive and excited. We are a family of adoptees. Each of us has a different story to tell, and our family of writers runs the gamut … domestic adoption, transracial adoption, foster care, international adoption and more. Some of our sisters are adopted parents as well as adoptees. I am always amazed at the diversity of voices.

November’s significance lies in a few adoption industry campaigns, National Adoption Month, Orphan Sunday and today … World Adoption Day.

The wonderful talents in the adoptee family have converged to make sure our voices are heard and seen as #validvoices. Filmmaker Bryan Tucker (Closure), created a wonderful video featuring the Lost Daughters voices.

Now, I look to you. Adoptees only. Join your family and tell your story below in the comments. Also note that I will be pulling out some of your comments to tweet this month. Let our voices ring out … loudly, honestly and collectively.

While frustrated with my old woman confusion, my son did help me create a MEME; and yes, he is the baby in the photograph.

24 October 2014

Korean Kin, Part 3 (final)

When I feel lonely, I turn to my Lost Daughters sisters. They know my pain, my confusion and my sadness. When G.O.A.’L asked me if I would have emotional support when I returned home, I said that my Lost Daughters sisters were my family and my support.

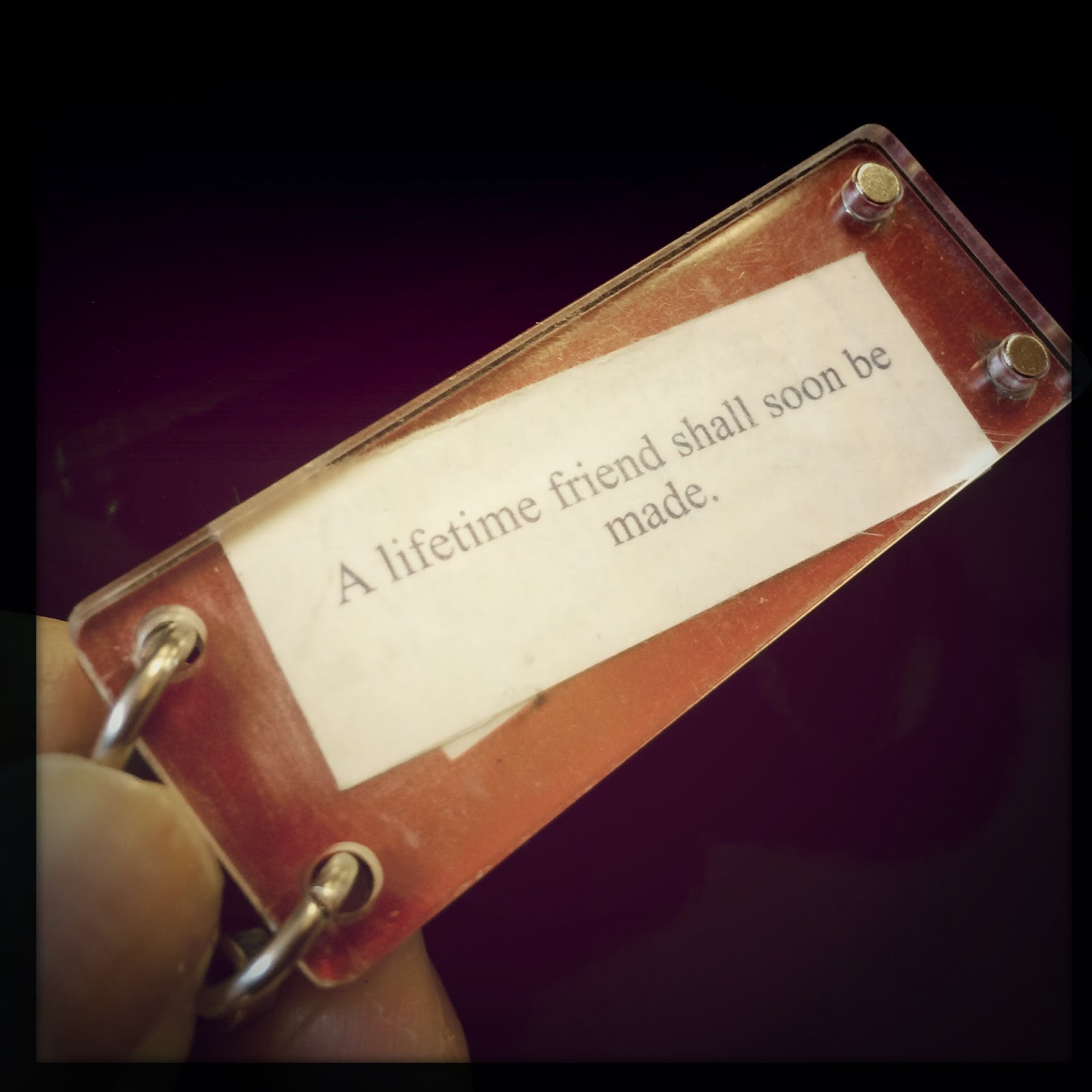

Just before leaving, I opened a fortune cookie to find this:

My friends rejoiced. “See! This will be a fabulous trip!”

My expectations were scattered. In my mind, I worked through all the permutations. Who I might find or not. Who might want to see me or not. Who might look like me or not.

I worried about my birth family, my adoptive family and my children. This trip would change me. I knew it. My family knew it. We were all anxious.

But once my feet hit the ground in Incheon, I felt the unspoken comfort of home. Like a long lost relative, John from G.O.A.’L, texted me as I moved through immigration and customs.

I was met with several happy, tired faces. Some spoke English, others Dutch and one French, but our faces were familiar. The next ten days brought personal disappointment and road blocks, wonderful food, many late night conversations at the BOA Guesthouse and a road trip to Gyeongju.

Before I knew it, our time was up. At the end of my journey, I wrote this:

“The plane takes off and tears are streaming from my eyes to streak my cheeks. I close my eyes in hopes of blinding the thoughts and images from the past ten days. The friends are so super special — my new family. ”

I had selected a beautiful handmade paper for my family room from a well-known calligrapher in Insadong. It was carefully rolled and stayed with me but would not fit in my suitcase. In my absent-minded fog, I left it on a counter outside security. Airport staff informed me that I could not retrieve it.

I was devastated. It seemed so silly to feel this way over two sheets of paper. I posted my sorrow on FaceBook.

My new KAD family of lost brothers and sisters came to my rescue. Two women made it their mission to find the paper as they were checking in for their European flights. The news that they had found it reached me just as I was boarding. Relief and joy overtook me. Not many people would risk delaying a flight to search for two sheets of paper, but these were no ordinary friends. They knew that my attachment to those two sheets of paper was not trivial.

All my life, I was told that I was “chosen,” and yet, I felt out of control. This time, I was surrounded by people who knew my fears firsthand. I had chosen them as family, and they brought great peace to me.

I miss my adoptee family, but now, I am embarking on a new search where the circle of family will widen. Check out this short film by Bryan Tucker, videographer from Closure, that introduces a new book by adult adoptees for teen adoptees and fostered youth. Dear Wonderful You, adoptees are your village.

Labels:

acceptance,

adopted,

adoptee,

adoptees,

adoption,

alike,

Closure,

Dear Wonderful You,

family,

friendship,

G.O.A.’L.,

Lost Daughters,

search,

teenagers

03 October 2014

Korean Kin, Part 2

Sadness. Overwhelming sadness is the only way I can describe how I feel about learning nothing new about my history before my adoption. I lost my adoptive mother in 2001, I lost my biological family in 1968, and I lost them again this year.

Loss seems to be a pervasive thing in my life. I accept that. The biggest blows in my life have been the loss of the women … my mother, my Grandma in Tennessee and my Abuelita in Puerto Rico. Losing them was like losing my compass. However, now, I understand the loss more. I knew loss long before I lost them.

Before these mothers, I had an original one. I know nothing about her except that she cared well for me until I was six months old. After I lost her, I found another woman, my foster mother, who would love me and build a bond with me. But then, I lost her too.

I had hoped that my interview with the Korean news agency, SBS, would allow me to find this second mother. But alas, that would not be. The only clues I was given came from the adoption agency social worker. She seemed surprised that I owned photographs of my foster mother. “In those days, only the wealthy could afford photographs such as these taken at home.” I have stared at these images since early childhood. They were sent to my parents after my first birthday by the adoption agency, but today, the agency has no record of who they are. I hold on to these words from my papers:

The moment my feet hit Korean soil, I felt at home. Comfortable and reassured. Included and content. No more wondering how I would cope with Korea.

If you haven’t read Part 1, you can find it here. Stay tuned for Part 3 … the silver lining.

Loss seems to be a pervasive thing in my life. I accept that. The biggest blows in my life have been the loss of the women … my mother, my Grandma in Tennessee and my Abuelita in Puerto Rico. Losing them was like losing my compass. However, now, I understand the loss more. I knew loss long before I lost them.

Before these mothers, I had an original one. I know nothing about her except that she cared well for me until I was six months old. After I lost her, I found another woman, my foster mother, who would love me and build a bond with me. But then, I lost her too.

I had hoped that my interview with the Korean news agency, SBS, would allow me to find this second mother. But alas, that would not be. The only clues I was given came from the adoption agency social worker. She seemed surprised that I owned photographs of my foster mother. “In those days, only the wealthy could afford photographs such as these taken at home.” I have stared at these images since early childhood. They were sent to my parents after my first birthday by the adoption agency, but today, the agency has no record of who they are. I hold on to these words from my papers:

“Is attached to her foster mother, and not shy of strangers. …” — Progress Report dated August 23, 1968.

“Sook Hyun is a happy and healthy girl, who enjoys a normal progress. When she came at first, she had a little herdship [sic] adjusting herself, but now she is a different girl, who is always cheerful and in good shape. She is loved a lot by her foster family and is expected to be a nice addition to her would-be adoptive parents.” — Progress Report dated December 11, 1968.A piece of me remains in Korea, in the corners of my foster mother’s mind.

The moment my feet hit Korean soil, I felt at home. Comfortable and reassured. Included and content. No more wondering how I would cope with Korea.

If you haven’t read Part 1, you can find it here. Stay tuned for Part 3 … the silver lining.

26 August 2014

“A DNA test is only as good as the database.”

I am riding on the bus … to O’hare for my trip to Korea. I am filled with so many emotions, I cannot fully explain them in words.

Having said that, the reality of the search hit me hardest when the itinerary for my trip arrived. In the next day or so, I will be swabbed for a DNA test. Many of my Lost Daughters’ sisters have already had such a test. They have found so many things about themselves via 23andMe and Ancestry.com.

I have always toyed with the idea of the DNA test in my mind, but this summer at KAAN, as I listened to the words of Bonnie LeRoy, I felt ambiguous relief as she said, “A DNA test is only as good as the database.”

For the domestic adoptees of the Lost Daughters, the test has in some cases been successful. Hearing Dr. Lee’s words, I realized that such a test may not be plausible for me, a Korean born adoptee. In order for my DNA to match someone in Korea’s, that person would need to test and access DNA records in the United States to find me.

As you know, the reasons for my search began with my children’s curiosity but have ended with my hope to never rob my birth mother. I feel as though I take one step forward, then pull myself two steps back. While I want to do this for others, I am not sure I want this for myself.

The prospect of this DNA test in Korea has made it all the more real. When I sit on my sofa in Wisconsin, there are many “what ifs” I can ponder, but to set foot in Korea and add my DNA to other Koreans’ …

Having said that, the reality of the search hit me hardest when the itinerary for my trip arrived. In the next day or so, I will be swabbed for a DNA test. Many of my Lost Daughters’ sisters have already had such a test. They have found so many things about themselves via 23andMe and Ancestry.com.

I have always toyed with the idea of the DNA test in my mind, but this summer at KAAN, as I listened to the words of Bonnie LeRoy, I felt ambiguous relief as she said, “A DNA test is only as good as the database.”

For the domestic adoptees of the Lost Daughters, the test has in some cases been successful. Hearing Dr. Lee’s words, I realized that such a test may not be plausible for me, a Korean born adoptee. In order for my DNA to match someone in Korea’s, that person would need to test and access DNA records in the United States to find me.

As you know, the reasons for my search began with my children’s curiosity but have ended with my hope to never rob my birth mother. I feel as though I take one step forward, then pull myself two steps back. While I want to do this for others, I am not sure I want this for myself.

The prospect of this DNA test in Korea has made it all the more real. When I sit on my sofa in Wisconsin, there are many “what ifs” I can ponder, but to set foot in Korea and add my DNA to other Koreans’ …

Labels:

birth mother,

Bonnie LeRoy,

DNA,

family,

fear,

KAAN,

Korea,

return

13 July 2014

Fear of Being Korean

Every time I look into my children’s eyes, I see pieces of me that I feel I do not know. In August, I journey to Korea with the help of G.O.A.’L, a Korean organization of adoptees who advocate for other adoptees.

I love finally having a physical connection through my children, but I struggle. I don’t want to make it about me. They are their own people. They are entitled to their own identities.

That said, as they have gotten older, they do question, and the tie to me is more evident. They suffer the ambiguity that I feel; they question this unknown family because frankly, it comes up almost every time we enter a clinic or hospital.

We are working through all this at a faster rate than I expected. The trip to Korea is in 43 days. My children are reluctant about my trip. They fear something … losing me … losing Papito (my father) … losing themselves in a family they want to know but are afraid to know.

I feel the same. I have had questions for so long, they live in my mind like all the other nerves that function as a part of my being alive. I have grown accustomed to them and kept them quiet for fear of hurting my parents. However, what I know now as an adult is that my father has always wanted this for me.

He wanted me to know the culture and history of Korea. He wanted me to know the food, the language and the customs. Yet, rural Tennessee was not the place for such knowing. Tennessee is a place of survival … a place to cherish kin and the Bible.

Once more, I see more clearly my father’s Puerto Rican culture was suppressed there. He jokes that when patients at the hospital where he works say, “You got an accent,” he retorts, “I didn’t have one until I got here.”

I see him feeling the ambivalence of being Puerto Rican, yet not … being Tennessean, but not. He knows too well my fears, and I take comfort that whatever happens in August will never break the tie I have to my family at home.

But I fear being Korean. I fear being Korean yet a stranger in my homeland. I fear being Korean but unable to converse with my Korean family. I fear being Korean because that might mean I am less Puerto Rican. I fear being Korean, but not recognizing the part of me that has tormented me my entire life … the part that kept me separate from others … the part that made me different … the part that elicited prejudice.

When I said I was “Korean, not Chinese” as a child, I had no idea how complicated that was.

I love finally having a physical connection through my children, but I struggle. I don’t want to make it about me. They are their own people. They are entitled to their own identities.

That said, as they have gotten older, they do question, and the tie to me is more evident. They suffer the ambiguity that I feel; they question this unknown family because frankly, it comes up almost every time we enter a clinic or hospital.

We are working through all this at a faster rate than I expected. The trip to Korea is in 43 days. My children are reluctant about my trip. They fear something … losing me … losing Papito (my father) … losing themselves in a family they want to know but are afraid to know.

I feel the same. I have had questions for so long, they live in my mind like all the other nerves that function as a part of my being alive. I have grown accustomed to them and kept them quiet for fear of hurting my parents. However, what I know now as an adult is that my father has always wanted this for me.

He wanted me to know the culture and history of Korea. He wanted me to know the food, the language and the customs. Yet, rural Tennessee was not the place for such knowing. Tennessee is a place of survival … a place to cherish kin and the Bible.

Once more, I see more clearly my father’s Puerto Rican culture was suppressed there. He jokes that when patients at the hospital where he works say, “You got an accent,” he retorts, “I didn’t have one until I got here.”

I see him feeling the ambivalence of being Puerto Rican, yet not … being Tennessean, but not. He knows too well my fears, and I take comfort that whatever happens in August will never break the tie I have to my family at home.

But I fear being Korean. I fear being Korean yet a stranger in my homeland. I fear being Korean but unable to converse with my Korean family. I fear being Korean because that might mean I am less Puerto Rican. I fear being Korean, but not recognizing the part of me that has tormented me my entire life … the part that kept me separate from others … the part that made me different … the part that elicited prejudice.

When I said I was “Korean, not Chinese” as a child, I had no idea how complicated that was.

Labels:

ambiguity,

biological child,

biological parents,

children,

Daddy,

family,

father,

fear,

G.O.A.’L.,

identity,

Korea,

Korean,

Puerto Rican,

return,

Tennessee

10 July 2014

#TBT

It’s Thursday. The feed floods with remembrances of babies, youngsters, bad hair days, 70s disco dress and 80s rebel wear. Proof we lived through the 80s.

Here’s one:

Seriously … bad.

I love seeing the photographs of others’ siblings and parents. The similarities in their anatomical features: the similar smiles, the same stance, mirrored features.

Last week, someone posted a photograph of her brother as a child. It was amazing to see her biological children’s faces in this image taken many years before they were born. I found myself typing about the similarities, but then, I stopped myself. She has one son who is adopted. Quickly, I hit the delete key.

Knowing her son might see my comment, I wanted to spare him the sadness of never sharing the sameness. I know that sadness; however, it was often tempered with my family forgetting my foreignness.

The birth of my children solidified my biological place in my own little family. I realize for many adoptive parents who, like my own, never thought they would see their eyes gaze up at them, that fact is so very difficult to bear. I empathize. I understand the joy an adoptee can bring to a childless couple … how we ease the pain. Yet, here I implore adoptive parents to recognize and address the added pain their adopted child experiences when she has no physical frame of reference.

Selfishly, I finally delight in the comments, “Oh, your son and daughter look just like you!” Bear with me. This time of seeing myself in another human being has brought me joy amidst the childhood pain of never experiencing this reflection of self in someone else.

Here’s one:

I love seeing the photographs of others’ siblings and parents. The similarities in their anatomical features: the similar smiles, the same stance, mirrored features.

Last week, someone posted a photograph of her brother as a child. It was amazing to see her biological children’s faces in this image taken many years before they were born. I found myself typing about the similarities, but then, I stopped myself. She has one son who is adopted. Quickly, I hit the delete key.

Knowing her son might see my comment, I wanted to spare him the sadness of never sharing the sameness. I know that sadness; however, it was often tempered with my family forgetting my foreignness.

The birth of my children solidified my biological place in my own little family. I realize for many adoptive parents who, like my own, never thought they would see their eyes gaze up at them, that fact is so very difficult to bear. I empathize. I understand the joy an adoptee can bring to a childless couple … how we ease the pain. Yet, here I implore adoptive parents to recognize and address the added pain their adopted child experiences when she has no physical frame of reference.

Selfishly, I finally delight in the comments, “Oh, your son and daughter look just like you!” Bear with me. This time of seeing myself in another human being has brought me joy amidst the childhood pain of never experiencing this reflection of self in someone else.

Labels:

#TBT,

adoptee,

biological child,

birth mother,

children,

family,

photographs

29 May 2014

The Lengths of Loyalty

At this moment, my father is intubated and riding in an ambulance to Knoxville, Tennessee. This is the man who I highlighted in this tweet.

This tweet came about after my last conversation with my father about my adoption search. As always, he reassured me and punctuated my right to know about my original country and family.

Loyalty is a legacy. While I had discussed my search with my father many times, my husband wanted me to discuss my open search with my father one more time. My husband feared that such actions would hurt my father.

I knew this to be untrue. Too many times, my father and I had discussed the possibility of my search. Books on Korea, his Korean dictionary, his affinity for Korean food were shared with me. I have never felt that I was not his or he mine. But loyalty works its way into my entire family.

Earlier this year, as my daughter was lamenting how far we are from family, she sighed and said, “Mom, I wish I had cousins.” I, of course, began rattling off the names of my sister’s daughter and my sister-in-law’s children. My daughter said, “No, I meant genetic cousins, like in Korea.”

And yet, after our visit to Puerto Rico, my daughter’s loyalty began to show.

“I want to know the heritage (Korean), but I don’t want to know my genetic family. I have cousins already. You can’t neglect the family you have. I don’t need to be blood-related to have family,” she told me.

I asked her how she felt in Puerto Rico.