Since the early 1990s, the lyrics and music of the Indigo Girls have mirrored themes in my life. They console me, comfort me and cajole me. I love that.

When they came to a town close to me or to a friend, I arranged child-minding to never miss them … Knoxville, Nashville, Denver, Charlottesville, Madison and Iowa City. Their concerts always felt like a family reunion … fans of all types resembled my life and my activism for equity and justice … that is, until I moved to the Mid-West and more specifically Madison.

There is something about seeing them in the South. Perhaps it is the kinship I have felt with them as Southerners. I love “Southland in the Springtime” which rarely plays in the Mid-West. But the overall prevailing camaraderie with the crowd is different.

Recently, they returned to Madison. This was my third concert of theirs since moving to Madison. I invited my Tennerican friend to come see them with me. He’s like a brother to me, a Puerto Rican with Tennessee ties. We were ecstatic! We arrived early and were within the first ten in line to go inside.

As we sat down, a young man sat next to me. Jovial and excited, we began a conversation. He offered to buy me a drink, though I declined. We waited. The space in front of us was a mosh pit, not exactly what I was accustom to, but from our seats, we could still see despite the crowd in front of us.

As the Indigo Girls entered the stage, we cheered. I told the man next to me that I was excited about seeing Lyris Hung. When I said this, he said, “Well, if I weren’t queer, I would do Amy hard. But I also love Asians and think I will end up with an Asian man someday. As a matter of fact, my friends call me ‘The Rice Queen’!”

I was in shock. A man who I had initially seen as a nice enough person was now showing signs of misogyny and racism. This was a precursor to more obnoxious behavior from this white, gay man.

Lyris Hung made her appearance on the stage with the Indigo Girls the year before, at concerts in Madison (on the same Overture Center stage) and in Iowa City. Seeing an Asian musician was a welcomed sight. Since seeing her in Madison and feeling the energy of the “Devil Went Down to Georgia,” I wanted to see more of what her contributions would be to the band that spoke to my heart.

As the set progressed, Amy played the song “Fishtails.” This song speaks of the loss of a father, and of course, it spoke to me since

my father’s passing was still an open wound. I had listened to it repeatedly since buying the album. It was the moment I was waiting for. But just as Amy poured her heart out to meet mine about our shared loss, a group of white women in the mosh pit decided to joke and laugh loudly. I was crushed and angry.

Approaching them, I said, “Do you mind taking this conversation outside? I am trying to enjoy this song.” This didn’t quite sink in; they looked at me, dazed. When I walked away, my friend saw them glaring at me. They continued to stare at me throughout the night and chatting amongst themselves like a cluster of sorority sisters, beers in hand and talking loudly. They only came to life with the music of “Galileo” and “Closer to Fine.”

My friend wanted to approach them during the concert, but he expressed his fear that he would be seen as a disruptive Puerto Rican man.

White Madisonians do not realize the prevailing scrutiny that people of color, especially Blacks and Latinos experience. Madison is painted as an idyllic, liberal college town. It is liberal … for whites.

White liberalism is a dangerous kind of liberalism where people believe that they cannot be racist because they hold other forms of liberalism high. They are active in liberal politics, the environment and issues surrounding gender equality, but only equality as it applies to whites. Now, not all Madisonians are this way, but the prevailing comfort and smugness of liberalism discredits any dissension in the ranks.

As the evening at the concert progressed, the white gay man decided to stand alone in front of his seat, despite the pleas from the women behind him. Addressing him as “Sir,” they politely asked him to sit in his seat or moved to the mosh pit. We all had chosen our seats for the luxury of sitting and listening; he refused to budge. He stood and scanned his phone, not at all paying attention to the music.

The women approached an usher and asked that someone talk with him. The usher refused. A white, stubborn man, regardless of his gender would not be asked to change his behavior. I just imagined the scene if it had been my friend, a Puerto Rican man standing in defiance. My friend was just as annoyed but recognized his place in this environment.

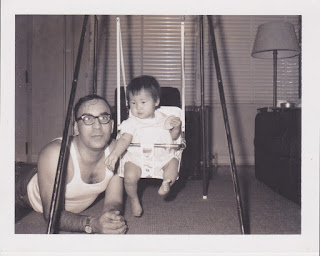

Despite the annoyances, we enjoyed our time together in a place filled with music that speaks volumes to us, and I was able to get photographs of Lyris to show

my girl at home. The image of an Asian woman successful in her musical pursuits.

I defended my background and the America I thought mine. Through tears, I told him he was generalizing. I told him of my family back in Tennessee. He laughed at my naïveté and my silly passion for a country. “My country sucks, but if you criticized it, I would NOT be in tears,” he told me.

I defended my background and the America I thought mine. Through tears, I told him he was generalizing. I told him of my family back in Tennessee. He laughed at my naïveté and my silly passion for a country. “My country sucks, but if you criticized it, I would NOT be in tears,” he told me.