The scene outside our room window.

Large groups of school kids, families and others flocked to the mountains, just as tourists did in my hometown at the foothills of the Smoky Mountains.

In those days, my grandmother cleaned at the local motel. The work was hard and paid little. Even though she is now gone, I always remember her worn hands whenever I stay at a hotel or motel. The women and men who clean rooms have the most thankless jobs.

They are invisible elves who come and clean the very things we hate to do in our own homes … the toilets, the bath drain, the sinks, the dishes and the bed linens.

Packing up today, our teenager decided he would not be doing the dishes before we left because he believed it was housekeeping’s job. Earlier, I had bumped into a young man that reminded me of my son … earphones in and listening to his music. As I stepped on the elevator, he smiled and skipped out the elevator and down the stairs. At first, I thought he was another young resort resident kid on a trip, most likely playing pranks on his fellow fieldtrippers. But later, I saw him pushing the cart of dirty linens down the hallway.

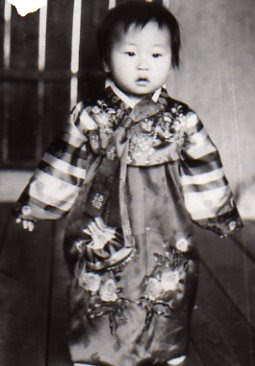

Flashing back to my own experiences of seeing my grandmother clean after really filthy folks, I lost my temper and told my teen that he needed to clean the dishes and help the housekeeping staff have a nice Christmas eve, one where the work would be less so that they could enjoy more time with their families. I did what I resent adoptive parents telling me. I told him he should be grateful that he could have such a vacation and not have to work as the young housekeeper did.

Later, I regretted my manner in engaging my son. But as we did our final sweep of the room before checkout, my teen offered his money to leave behind in the room.