Marriage is hard. It’s exhilarating at first; then the relationship slides into routine. Add children, and it shifts

from the couple to the kids.

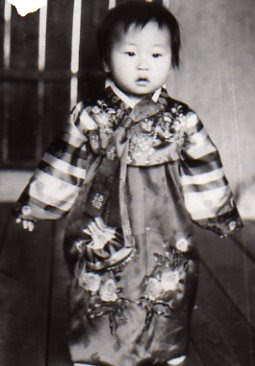

As an adoptee, this is bliss until the moment you realize you have some deep-seeded racial identity issues. It isn’t that I didn’t know I had them, I knew I wanted to be white. But I never felt strong enough to speak for myself,

so I stayed silent,

dated only white guys and

you know the rest of that story.

The strength in our marriage is that we are able to adapt and learn. Sometimes, the learning is hard for both of us, as we learn that we are the two extremes that play out in our children. Many times, I get frustrated and angry without explaining why. That is truly tough on my husband.

Monday, he took the day off so that we could take a much needed family break at

Lotte World Adventure, “the largest indoor amusement park in the world.” There was joy and excitement. We were taking selfies and “wrecking noobs.”

No one spoke English, and we often wandered around not really knowing what to do. Of course,

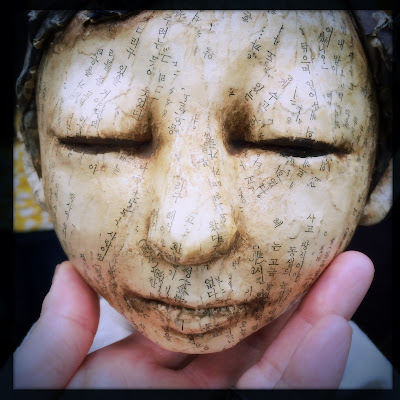

as usual, when we tried speaking or ordering, the cashier would always look to me and talk to me in Korean. Then, my sheepish voice would reveal that I was an American. That’s a running theme here … Korean women speaking for the family as a whole. But my voice is again silenced in that role.

My husband can speak English, and Koreans rush to help him and find translation. Or they just throw up their hands and make a face.

Two distinct things happened to us that day. We learned about white privilege in Korea, and how it isn’t the same as just plain bullying.

The first incident happened as we waited to give one another whiplash on the bumper cars. As we inched up to the front of the line, the ticket woman asked us how many we had in our party. My husband held up his four fingers. She counted and allowed the two women behind me to enter and take the last two remaining cars. This, of course, sparked our families competitive side.

We watched for the fastest, most responsive cars and yelled out to one another what car we were eyeing. It was sheer family fun! As the last group cleared the track, my husband, son and daughter began to rush toward the cars, but the ticket taker stopped me at the gate and asked for my ticket. She hadn’t asked my husband for his ticket, and my ticket was in my husband’s pocket.

I called his name once, louder a second time and then I shouted his name in panic the third time, telling him I needed my ticket. He was trying to seat himself in his car, so he was a bit perturbed that I had yelled at him. He showed my ticket, and I was allowed to enter the arena.

My head was spinning.

“Hadn’t she just a few minutes before counted us as a party of four? And why would she separate me from my family?” I felt stupid and less than. Once we got off the ride, my daughter sulked saying she was embarrassed by what had happened … Mom yelled and Dad was visibly irritated.

I apologized, and we moved on to our next adventure. But as we waited again for the next ride, we had the same thing happen. This ride took families, so we were once again counted. When my husband gave the young woman our four tickets, she questioned where the fourth person was, and my husband had to point out that I was his wife.

There are many things I have tried to rationalize …

“maybe the Korean women hold the tickets, maybe my kids look more like my husband and less like me, maybe I just do not look like I belong in my family.”

As we took off in our fake hot air balloon, I let my family know how I was feeling. This second time, they came to the realization that I was indeed not seen as part of our family. I was othered, and it stung just as it always does.

In the old days, when I spoke to adoptive parents and social workers, I advised them to make sure they had put themselves in a situation where they were the minority. But that day, I realized that

even if a white person is the minority, he or she still holds white privilege and is afforded things based on that role in our world.

When my husband and I lived in Rwanda, we were in the minority, but he was viewed as superior, and I was inappropriately touched and questioned by teenage soldiers. As a Korean woman, I feel less than no matter where I am. Most times, I am a lone Asian woman, so there are no allies. In my aloneness, I am quiet and try to blend into the background.

Having said this, I want to tell you what happened next. Our last ride was a Magic Pass ride, so we we were able to miss some of the queuing. Once we got to the final part of the line, I noticed two teen boys behind us staring at my son and making rude gestures about him. They were looking at my son, making faces and laughing. When I realized what was happening, I began to stare at them with disdain. They noticed my stare and began to hide behind others in line between us.

Feeling that I had stopped it before my son noticed, I moved my gaze to the front of the line. Here I witnessed a group of eight teenage boys. The most attractive one wore a white shirt and a Kpop hairdo. He was making fun of my husband’s nose. Using his hands, he acted as though he had a large nose and made odd gestures with his eyes too. The other seven laughed and looked back at my family.

Again, I stared at them, showing my disgust. They, too, looked away and hid. They would quickly glance to see if I was still there, and my laser gaze met theirs. I wanted them to feel ashamed and scorned. I whispered to my husband that this was happening so that he could stare at the eight in front of us, and I could stare at the two behind.

Once that ride was over, so was I. We left Lotte World and moved to our favorite restaurant. We arrived to the cheerful staff who always serve us. They were chatty and friendly. Dinner time is our family time to discuss our day. My husband opened with discussion about the eight boys. He asked me if I wanted to tell the story.

But I began with the story of the two boys. My husband asked why I started with that story, but I felt our son needed to know he was being targeted as much as he needed to know that his father was targeted too. You see, in my mind, these were not instances of racism against my husband as a white man, but instances of

bullying. The boys would make fun of anything different, and it wasn’t based on a power structure.

My kids understand so much already about racism and bullies, it seems fair they know the full story. They see their parents disagree, discuss and assess together. It isn’t always pretty, but they know we love one another and that disagreements are not cause for divorce in our family. There is respect. While it may take us time to fully understand, we work to see the other’s side.

We have a few more months here in Korea. I doubt this will be the last day we will need to detox, but boy, was it a doozy.