In the past few weeks, our community of adoptees lost two souls … one a 14-year-old Korean girl, the other a

deported 40-something Korean man.

Each one suffered the loneliness associated with our lives as part of a diaspora

we never chose.

Adoptees are

four times more likely to attempt suicide. We have also learned to mask our true emotions; it is our way of survival.

So many aspects of our lives bring us to moments where we feel no self worth. The

family tree, the

comments about how relatives take one trait from another relative, the

racists taunts that further separate us from our adoptive families … all these experiences build the wall between us and our adoptive communities.

And in some cases, we are rejected and sent from the only country we know (The United States) to our birth place … because our American guardians (our adoptive parents) have never bothered to legitimize us as citizens. Such was the case of

Philip Clay.

His death has hit me so hard. Just a month ago, I returned from a three-week trip to my home country. The return ravaged me. Just stepping off the plane and back into the Midwest reminded me that I was

a stranger here … and unwanted.

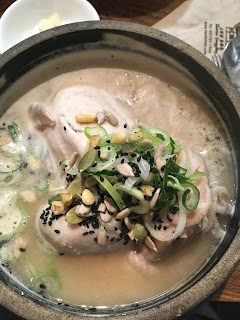

In Seoul, I felt joy and sorrow, but the sorrow was bearable. A community of adoptee friends and the

tastes and smells of my infanthood comforted me. Korea allowed me to express my feelings and roam as just another Korean.

In the United States, I felt sorrow and hopelessness.

In the US, I feel owned by my agency. I am reminded that my wishes are not mine to hold.

My desires to be a full person with a history go unnoticed. I am not considered the person with human rights that the United Nations Convention declared, but the transaction that must abide by the State of Oregon’s laws. I am not an individual, but the “child” of two deceased, adoptive parents. I am nobody.

As I sank deeper into myself, my small family could not understand. I was draining the life out of us all. So … I sat alone. I didn’t want to leave home. Work, a joy I once had, began to drain me further. And I snapped at those I loved. Like a wounded animal, I hid and hissed at those who came near.

Depression keeps us in shackles. It shuts us in seclusion as we smile and pretend. We laugh in public, yet cower in the quiet of our rooms. We make others happy and then sleep little as our mind races to find some sliver of self worth. Then you hear that another adoptee has died at her own hand. You wonder how that would feel to not hurt anymore. You wonder if your soul would truly live beyond the pain of this world.

Some wonder how you can disregard the good in your life and contemplate such selfish thoughts, but know that once you dig a hole, the light no longer streams in. You want the pain to stop. You want peace.

I finally got to a point where I could no longer hold my sorrow and wear a mask. One friend noticed and arranged time for us to just talk (or rather, he was gracious to just listen). I began to understand that the hole was mine but that I could scale it!

Our community is full of people who understand. I only wish we were better at connecting. Social media sites and conferences have helped, but there is still more work to be done. We need one another. But asking for that help is difficult.

Our struggles and our narratives as adoptees are valuable. The mental health profession needs more professionals with skills that meet the needs of adoptees and not just the needs of adoptive parents. There are many adoptees doing the work as therapists, but it should not be solely their responsibility. The profession as a whole can learn from them. We need them before we lose any more from our community.

If you feel despair, please call the National Suicide Hotline at 1-800-273-8255.

Also, feel free to write me here. I promise to write back.