As I have been reading research on transracial adoptees, I am realizing that while we have similar stories to share, we also have widely varying views on adoptions. Logically, we are different people and no two of us are alike.

The interesting thing for me, is that my feelings about race align more with my first generation Asian friends (as introduced

here) than with Asian adoptees.

My first generation Asian friends, Adrienne and Katherine, were Asian minorities in their childhood communities, much like me. Adrienne blogs about her small town experience:

“The moment I first appeared on the playground of my new elementary

school, the noisy chatter and laughter of children at play abruptly

ceased, as if someone had pushed a magic mute button. Feverish

whispering closely followed the eerie hush that had suddenly descended

upon the playground. Little blond heads leaned in close together as the

children conferred with each other in obvious bewilderment and

consternation at the appearance of this alien in their midst.

Innocently, they tried to work out how my face got so very flat, whether

my eyes hurt all the time, or whether one would eventually get used to

the pain of having eyes like mine … ” (Read the full post here.)

Katherine recalls her childhood in this way:

“When I was growing up my grandmother used to say to me, “You

may feel like you are just like them, but no matter how you feel, you will

never look like them.”

I was born in the U.S., the daughter of two Asian immigrants

who came here in the 1960s for graduate school. My parents disagreed on the extent of our

assimilation into American culture: my father spoke to me only in English while

my mother spoke to me primarily in her native tongue. My father was more

adventurous in terms of eating non-Asian foods; my mother was less so. For me,

there was no question—I felt 100% American and wanted to be just like the other

kids, and anything that set me apart from them was a source of burning

embarrassment. I begged my mother to cook American dinners like macaroni and

cheese and spaghetti and meatballs, buy me the same kinds of clothes and shoes

that the other kids wore, and fiercely resisted her attempts to teach me any

other language that was not English. Every day at school, and while playing in

the neighborhood, I saw only white children—and after a while I assumed I was

one of them.

But I wasn’t. Some kids would make faces at me, pulling at

their eyes until they were all squinty, pretend to speak Chinese, and laugh.

Some would tease me and ask me to “say something Chinese” as if I was some kind

of circus freak show. And of course there was the “Chinese, Japanese, dirty

knees…” taunt that was said in a sing song-y voice. It seemed like every time I

started to forget that I was different, I was reminded that indeed I was. Only when I went to college in New York City and saw first hand

the incredible amount of diversity did I realize what I was: a ‘banana.’ Yellow on the outside, white on

the inside.

I’ve lost track of the number of times an Asian

person has approached me and started speaking to me in Chinese, assuming that

I’m fluent in Chinese because of how I look.

On fewer occasions, I’ve had Caucasian people compliment me on how well

I speak English, assuming that English was not my native language because of

how I look. Time and time again I’m reminded of the potential disconnect

between how I perceive myself and how others may perceive me. All people face

this problem to some extent, but for first-generation children of immigrants

who are caught between two cultures and who grew up without the benefit of

racial diversity—the problem becomes especially complicated.”

Adrienne, Katherine and I are very proud Asian

women. I stress the word, “women” because as I have written about in the post

The Ideal Beauty, I believe some of our past insecurities stemmed from the portrayal of girls and women in the media. When young girls are exposed to blond bombshells (think Cinderella, Barbie and the girls of Teen and Seventeen magazine), we and our non-Asian peers believe that is what we should be. Asians are virtually absent from our American media culture.

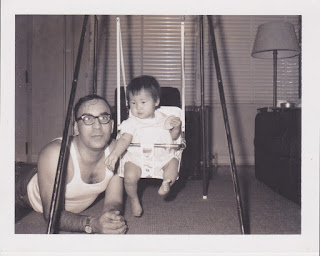

My mother was fully aware of the one-sided representations. She made sure I had Asian dolls, including dolls from Japan, Korea, Vietnam and of course the Asian baby doll.

Notice, however, that my little sister clutches a blond doll. While my sister is half Caucasian, she is also half Puerto Rican. In the 1970s, there weren’t many brunette dolls, let alone Hispanic ones. My sister clutched her blond dolls until the introduction of the Darcy dolls, sporting not only a blond, but a brunette and a red-head.

While we all had our struggles with our identities, I believe that

every person, adopted or not, struggles with his or her appearance intensely through adolescence and continually throughout life. Each person also resolves personal struggles in his or her unique way.

I enjoy the fact that I can text Adrienne and Katherine my photos of Asian market wares, only to find that we are having parallel experiences. (See Adrienne’s funny photographic tale

here.) Their mothers are teaching them, and in turn, they teach me.

Adrienne’s parents inspire her and me. Her recent

post summed up her feelings:

“At times I’ve felt like this was more their country than my own, even

though I was born and raised here. Thanks to my patriotic parents, I’ve

attended schools and have hung out with people who have tended to regard

patriotism with suspicion – as something corny and anachronistic. I

think it was only when I began to travel abroad that I realized how very

much I do appreciate this country and how much there is to love about

it.

‘THAT’S America,’ where nothing is impossible and where there are people

hard at work making sure wrongs are eventually righted, and where there

is a process to ensure that they are. That’s my parents’ America, and

I’m glad to be living in it too.”

Yes, and in this country, we can freely be who we want to be … say things as we choose … even experience other cultures. That’s our America!