Imagine being ethnically different from your classmates. Imagine feeling completely American, but knowing you aren’t quite like those around you. Imagine your fear in others discovering who you really are.

International adoptees feel this way. While we may feel out of place in school, in our community and sometimes in our home, we possess an identity. Almost immediately we become American citizens, courtesy of our adoptive families.

Now, imagine if you brought here at a young age, feel a connection with your community, but cannot fully enjoy being American solely because of where you were born?

The immigration reform issue has touched me. More specifically, four extremely brave, young people have been on my mind. Their stories can be found on the website, The Dream is Now. I encourage you to watch the trailer. Much of what they say has played over and over in my head.

Mayra, who is secretly taping her segment says, “I didn’t choose to come here. It was a decision my parents made for me in order to give me a better life.”

Osmar says, “I’m full American. I speak English; I know the culture. I am from here.”

I have said some of these things, and I suspect that other international adoptees have felt some of these feelings. But that is as far as the similarities go. Adoptees are able to pursue college scholarships and degrees. We are granted all the benefits of being American.

The interesting thing is that the Dreamers, too, have lived here as long as many international adoptees. They share similar experiences that relate to their ethnicity, while feeling completely American.

Their faces could be our faces. Their voices could be our voices. Their dreams are our dreams.

With my citizenship, I hope to make a difference in the lives of my fellow dreamers. Go Dreamers!

18 February 2013

14 February 2013

Our Last Valentine’s Day

In 1993, my mother and I shared Valentine’s Day. Each of us would have been alone that Valentine’s Day, had we not had each other.

For me, that day was V-Day or VD. I celebrated it as a day to enjoy my independence from the vagaries of love [LUUUUUhV].

My mother saw it as a day to celebrate her role as a mother. Our 1993 Valentine’s Day was the last one we had before I found another love. She would always remember this day in the years to follow.

In those following Valentine’s Day phone calls she would say, “Remember our last Valentine’s Day alone? We had drinks at Red Lobster and then moved on to the Spaghetti Warehouse. Remember?”

My response would be, “Yes, Mom. I remember. You loved downtown Knoxville. It reminded you of your days as a single woman, right?”

“I loved that we were spending THAT night together,” she would reply with a little sadness in her voice.

In March of 1993, I found the man who insisted that he not complete me, but complement me. It was a whirlwind.

We dated and moved in together that following September, against my mother’s wishes. That Valentine’s Day in 1994 she would be despondent.

For my mother, I think she felt her love had been replaced. On outward appearances, yes. Deep inside though, I still loved my mother as strongly as I had that prior Valentine’s Day.

She would feel much better about this “replacement” when the man who had “taken” me “away from her” proposed in September of 1994. This became the point of healing.

She had a wedding to plan, but it was still extremely painful for her to let go of her first child. My mother was not shy about expressing her feelings … to me and my future husband.

I still see the mixture of pain and pride in her face in this photograph taken at our wedding (Image by Rob Heller).

Someday, I will feel this pain in the same way. But for now, I enjoy the valentines my children give me and remember that evening so long ago at the Spaghetti Warehouse in Knoxville’s Old City.

For me, that day was V-Day or VD. I celebrated it as a day to enjoy my independence from the vagaries of love [LUUUUUhV].

My mother saw it as a day to celebrate her role as a mother. Our 1993 Valentine’s Day was the last one we had before I found another love. She would always remember this day in the years to follow.

In those following Valentine’s Day phone calls she would say, “Remember our last Valentine’s Day alone? We had drinks at Red Lobster and then moved on to the Spaghetti Warehouse. Remember?”

My response would be, “Yes, Mom. I remember. You loved downtown Knoxville. It reminded you of your days as a single woman, right?”

“I loved that we were spending THAT night together,” she would reply with a little sadness in her voice.

In March of 1993, I found the man who insisted that he not complete me, but complement me. It was a whirlwind.

We dated and moved in together that following September, against my mother’s wishes. That Valentine’s Day in 1994 she would be despondent.

For my mother, I think she felt her love had been replaced. On outward appearances, yes. Deep inside though, I still loved my mother as strongly as I had that prior Valentine’s Day.

She would feel much better about this “replacement” when the man who had “taken” me “away from her” proposed in September of 1994. This became the point of healing.

She had a wedding to plan, but it was still extremely painful for her to let go of her first child. My mother was not shy about expressing her feelings … to me and my future husband.

I still see the mixture of pain and pride in her face in this photograph taken at our wedding (Image by Rob Heller).

Someday, I will feel this pain in the same way. But for now, I enjoy the valentines my children give me and remember that evening so long ago at the Spaghetti Warehouse in Knoxville’s Old City.

Labels:

husband,

love,

mom,

mother,

Red Lobster,

Spaghetti Factory,

Valentine's Day,

wedding

05 February 2013

Mi Papi

My name reminds me of my heritage. There are palms and beaches. I hear the constant beat of the rhythm of the island. Adobo Pollochon fills my kitchen with smells from my childhood. I am Puertorriqueña. It all began in August of 1968.

Of course he had to cuddle me and our dog. She wasn’t going to be replaced by this new walking being.

I will forever be Daddy’s Girl.

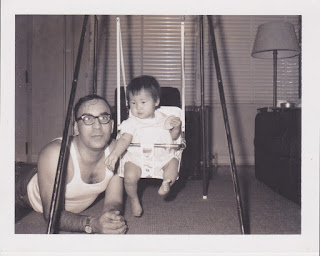

Prompted by my introduction letter, my father, recovering from surgery, took early medical leave to fly to Korea to meet me. He would forever wear a long scar, one that started small but stretched upon carrying all the bags for the trip.

Our meeting included several days of me becoming accustom to my parents. I think I was pretty comfortable.

I was instantly “Daddy’s Girl.” I followed my father wherever he went. I was his shadow.

His time in Korea, at the end of the Korean War, helped him acquire a taste for Korean food. When we are together, he often asks if there’s a Korean restaurant, and when he visits our favorite Korean restaurant in Knoxville, Tennessee, he texts me to let me know. He cannot have his kimchi without thinking of me.

Tucked away, I have his 1950s Korean/English dictionary. He tried to teach me Korean greetings, but I was more interested in the fun Spanish rhymes he would say.

Of course he had to cuddle me and our dog. She wasn’t going to be replaced by this new walking being.

I was introduced at the age of two to my Puerto Rican relatives. The island welcomed me, and I met mi Abuelita, mi Bisabuelita Ita and mi tio y las titis. The smells of the island kitchens still infiltrate my Wisconsin kitchen … especially in the cold months when I need the comfort of arroz y tostones.

My father’s family has committed the same unconditional love that forgets my biological race. In 2000, I brought my infant son to Puerto Rico to introduce him to the island, a land of abrazos y besos. My cousin, Richie, took us to the City Hall of Guayama and found my great grandfather’s portrait. He was the first Enrique. Richie proudly held my son against the portrait and proclaimed that my son looked just like his great-great grandfather, a former mayor of the town.

Quite a resemblance? ¿Verdad?

Enrique … that name has been passed on to every male in the family, but I broke the tradition. My stubborn will missed the subtle cues from my father in phrases like “What do you think about ‘Enrique’ or ‘Fernando’?” I realized my mistake when all the relatives asked how I came to my son’s name. Luckily, I have gotten some redemption now that my son is taking Spanish in school and has taken on the name “Enrique” for his class.

I speak of my mother often since I cannot see or speak with her, but my father is a constant presence in my life. I feel blessed for every day I have him to cuddle my children.

They are proud to have their Latino names and their Papito. They laugh when he uses his fart machine, they enjoy fishing with him as I did, and they admire his oil painting skills.

I am often reminded of the old audio reels from my father’s years in Vietnam. We were separated. I

turned three in Tennessee, but I missed him. I cannot imagine now the

pain my mother felt being so far away from her husband, or his pain at

leaving us and not knowing if he would return. He tells me that he would

often listen to the reel of me saying over and over, “Daddy, Daddy, Daddy! I want my daddy!”

He returned safely to later share one of the most treasured days of my adulthood.

Labels:

Abuelita,

Adobo Pollochon,

arroz y tostones,

Bisabuelita,

Daddy,

Daddy's Girl,

Enrique,

father,

Guayama,

kimchee,

kimchi,

Knoxville,

Korea,

Korean restaurant,

Puerto Rican,

tio,

titi,

unconditional love

03 February 2013

The faces we are born to wear …

As I have been reading research on transracial adoptees, I am realizing that while we have similar stories to share, we also have widely varying views on adoptions. Logically, we are different people and no two of us are alike.

The interesting thing for me, is that my feelings about race align more with my first generation Asian friends (as introduced here) than with Asian adoptees.

My first generation Asian friends, Adrienne and Katherine, were Asian minorities in their childhood communities, much like me. Adrienne blogs about her small town experience:

My mother was fully aware of the one-sided representations. She made sure I had Asian dolls, including dolls from Japan, Korea, Vietnam and of course the Asian baby doll.

Notice, however, that my little sister clutches a blond doll. While my sister is half Caucasian, she is also half Puerto Rican. In the 1970s, there weren’t many brunette dolls, let alone Hispanic ones. My sister clutched her blond dolls until the introduction of the Darcy dolls, sporting not only a blond, but a brunette and a red-head.

While we all had our struggles with our identities, I believe that every person, adopted or not, struggles with his or her appearance intensely through adolescence and continually throughout life. Each person also resolves personal struggles in his or her unique way.

I enjoy the fact that I can text Adrienne and Katherine my photos of Asian market wares, only to find that we are having parallel experiences. (See Adrienne’s funny photographic tale here.) Their mothers are teaching them, and in turn, they teach me.

Adrienne’s parents inspire her and me. Her recent post summed up her feelings:

The interesting thing for me, is that my feelings about race align more with my first generation Asian friends (as introduced here) than with Asian adoptees.

My first generation Asian friends, Adrienne and Katherine, were Asian minorities in their childhood communities, much like me. Adrienne blogs about her small town experience:

“The moment I first appeared on the playground of my new elementary school, the noisy chatter and laughter of children at play abruptly ceased, as if someone had pushed a magic mute button. Feverish whispering closely followed the eerie hush that had suddenly descended upon the playground. Little blond heads leaned in close together as the children conferred with each other in obvious bewilderment and consternation at the appearance of this alien in their midst. Innocently, they tried to work out how my face got so very flat, whether my eyes hurt all the time, or whether one would eventually get used to the pain of having eyes like mine … ” (Read the full post here.)Katherine recalls her childhood in this way:

Adrienne, Katherine and I are very proud Asian women. I stress the word, “women” because as I have written about in the post The Ideal Beauty, I believe some of our past insecurities stemmed from the portrayal of girls and women in the media. When young girls are exposed to blond bombshells (think Cinderella, Barbie and the girls of Teen and Seventeen magazine), we and our non-Asian peers believe that is what we should be. Asians are virtually absent from our American media culture.“When I was growing up my grandmother used to say to me, “You may feel like you are just like them, but no matter how you feel, you will never look like them.”

I was born in the U.S., the daughter of two Asian immigrants who came here in the 1960s for graduate school. My parents disagreed on the extent of our assimilation into American culture: my father spoke to me only in English while my mother spoke to me primarily in her native tongue. My father was more adventurous in terms of eating non-Asian foods; my mother was less so. For me, there was no question—I felt 100% American and wanted to be just like the other kids, and anything that set me apart from them was a source of burning embarrassment. I begged my mother to cook American dinners like macaroni and cheese and spaghetti and meatballs, buy me the same kinds of clothes and shoes that the other kids wore, and fiercely resisted her attempts to teach me any other language that was not English. Every day at school, and while playing in the neighborhood, I saw only white children—and after a while I assumed I was one of them.

But I wasn’t. Some kids would make faces at me, pulling at their eyes until they were all squinty, pretend to speak Chinese, and laugh. Some would tease me and ask me to “say something Chinese” as if I was some kind of circus freak show. And of course there was the “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees…” taunt that was said in a sing song-y voice. It seemed like every time I started to forget that I was different, I was reminded that indeed I was. Only when I went to college in New York City and saw first hand the incredible amount of diversity did I realize what I was: a ‘banana.’ Yellow on the outside, white on the inside.

I’ve lost track of the number of times an Asian person has approached me and started speaking to me in Chinese, assuming that I’m fluent in Chinese because of how I look. On fewer occasions, I’ve had Caucasian people compliment me on how well I speak English, assuming that English was not my native language because of how I look. Time and time again I’m reminded of the potential disconnect between how I perceive myself and how others may perceive me. All people face this problem to some extent, but for first-generation children of immigrants who are caught between two cultures and who grew up without the benefit of racial diversity—the problem becomes especially complicated.”

My mother was fully aware of the one-sided representations. She made sure I had Asian dolls, including dolls from Japan, Korea, Vietnam and of course the Asian baby doll.

Notice, however, that my little sister clutches a blond doll. While my sister is half Caucasian, she is also half Puerto Rican. In the 1970s, there weren’t many brunette dolls, let alone Hispanic ones. My sister clutched her blond dolls until the introduction of the Darcy dolls, sporting not only a blond, but a brunette and a red-head.

While we all had our struggles with our identities, I believe that every person, adopted or not, struggles with his or her appearance intensely through adolescence and continually throughout life. Each person also resolves personal struggles in his or her unique way.

I enjoy the fact that I can text Adrienne and Katherine my photos of Asian market wares, only to find that we are having parallel experiences. (See Adrienne’s funny photographic tale here.) Their mothers are teaching them, and in turn, they teach me.

Adrienne’s parents inspire her and me. Her recent post summed up her feelings:

“At times I’ve felt like this was more their country than my own, even though I was born and raised here. Thanks to my patriotic parents, I’ve attended schools and have hung out with people who have tended to regard patriotism with suspicion – as something corny and anachronistic. I think it was only when I began to travel abroad that I realized how very much I do appreciate this country and how much there is to love about it.Yes, and in this country, we can freely be who we want to be … say things as we choose … even experience other cultures. That’s our America!

‘THAT’S America,’ where nothing is impossible and where there are people hard at work making sure wrongs are eventually righted, and where there is a process to ensure that they are. That’s my parents’ America, and I’m glad to be living in it too.”

Labels:

adolescence,

adoptee,

America,

Asian,

Barbie,

blond,

bullying,

Cinderella,

culture,

doll,

first generation,

friendship,

Hispanic,

media,

minorities,

patriotism,

Puerto Rican,

racism,

struggles,

women

02 February 2013

Love is enough.

The subtitle for Barb Lee’s Adopted film is “When love is not enough …”. What kind of love is she talking about here?

I argue that love is enough.

The love I know came in the form of handmade, Korean clothes for me and my entire brownie troop. That love also displayed all my Asian dolls on shelves in my room.

That love stood between me and the bullies who hurled their personal insults and attacks at her.

That love forgot that I couldn’t bear her red-headed grandchildren.

That love wore small, silver Korean shoes (Hwahye) on her charm bracelet.

That love cried as hard as I did on the day I moved to Rwanda, shortly after my wedding.

That love wrote letters almost daily and sent them across the ocean to a post box in Kigali.

That love’s eyes twinkled the first day they set their sights on her first grandson … this, despite the fact that her lips were silenced by a stroke.

That love worked tirelessly to be able to have this moment with her first grandchild.

She left us twelve years ago on this day. But her love is here and growing in me, my sister and our children. Her love will forever be with us, and that is enough.

I argue that love is enough.

The love I know came in the form of handmade, Korean clothes for me and my entire brownie troop. That love also displayed all my Asian dolls on shelves in my room.

That love stood between me and the bullies who hurled their personal insults and attacks at her.

That love forgot that I couldn’t bear her red-headed grandchildren.

That love wore small, silver Korean shoes (Hwahye) on her charm bracelet.

That love cried as hard as I did on the day I moved to Rwanda, shortly after my wedding.

That love wrote letters almost daily and sent them across the ocean to a post box in Kigali.

That love’s eyes twinkled the first day they set their sights on her first grandson … this, despite the fact that her lips were silenced by a stroke.

That love worked tirelessly to be able to have this moment with her first grandchild.

She left us twelve years ago on this day. But her love is here and growing in me, my sister and our children. Her love will forever be with us, and that is enough.

28 January 2013

The Road Taken

The film, Adopted, was loaned to me to start me on a journey …

The problem is, I don’t want the angry journey portrayed in this movie through the adult adoptee, Jennifer. I am not her, nor do I feel as she does. I have never felt abandoned.

I identify more with her adoptive mother who says, “I think I probably remember a lot more details about picking Jenny up from the airport than I do about giving birth to Eric.”

Yet in search of her “core validation,” this young woman continues to lash out at her parents through snide comments and hurtful rejection. She forces a journey on her parents that they have made and are ending. Both her mother and father are dying of cancer.

I understand her recollections of racism outside of the home; I lived through those same racial jokes (see examples in this post). Unlike her, I experienced these moments with my family. When children chanted racial insults, my mother rushed up and confronted them. She faced their hurtful words as they shouted, “Come get us you big, fat hippopotamus!”

From day one, we all were a part of the journey. My mother was my best friend. I shared all the hurt with her. We talked through it. The adoptee, Jennifer, did not share, and now all the pent-up 9-year-old anger has surfaced in a thirty-something young woman.

She talks of “being authentic and real,” but I pose that your reality is what you make of it. I pose that individuals are different. While every adoption story does not end like Jennifer’s or mine, there are varying degrees of acceptance, abandonment and unconditional love.

The adoption story isn’t just about the well-being of the adoptee, as Jennifer would like us to believe. If it is, in fact, as Jennifer wishes, a journey they all take together, there should be some sensitivity for the adoptive parent.

Recently I have spoken of starting an adoptee’s journey, but more precisely, it is just a new chapter in my life … one of sharing parallel experiences, laughing at similarities (like all the vacuuming and couponing), and learning new stories.

I appreciate the different stories, but my life is full of wonderful things.

My daughter recently summed it up, saying, “If you weren’t adopted, I wouldn’t be here and we wouldn’t be with Daddy.”

I am content with the road I have taken.

The problem is, I don’t want the angry journey portrayed in this movie through the adult adoptee, Jennifer. I am not her, nor do I feel as she does. I have never felt abandoned.

I identify more with her adoptive mother who says, “I think I probably remember a lot more details about picking Jenny up from the airport than I do about giving birth to Eric.”

Yet in search of her “core validation,” this young woman continues to lash out at her parents through snide comments and hurtful rejection. She forces a journey on her parents that they have made and are ending. Both her mother and father are dying of cancer.

I understand her recollections of racism outside of the home; I lived through those same racial jokes (see examples in this post). Unlike her, I experienced these moments with my family. When children chanted racial insults, my mother rushed up and confronted them. She faced their hurtful words as they shouted, “Come get us you big, fat hippopotamus!”

From day one, we all were a part of the journey. My mother was my best friend. I shared all the hurt with her. We talked through it. The adoptee, Jennifer, did not share, and now all the pent-up 9-year-old anger has surfaced in a thirty-something young woman.

She talks of “being authentic and real,” but I pose that your reality is what you make of it. I pose that individuals are different. While every adoption story does not end like Jennifer’s or mine, there are varying degrees of acceptance, abandonment and unconditional love.

The adoption story isn’t just about the well-being of the adoptee, as Jennifer would like us to believe. If it is, in fact, as Jennifer wishes, a journey they all take together, there should be some sensitivity for the adoptive parent.

Recently I have spoken of starting an adoptee’s journey, but more precisely, it is just a new chapter in my life … one of sharing parallel experiences, laughing at similarities (like all the vacuuming and couponing), and learning new stories.

I appreciate the different stories, but my life is full of wonderful things.

My daughter recently summed it up, saying, “If you weren’t adopted, I wouldn’t be here and we wouldn’t be with Daddy.”

I am content with the road I have taken.

18 January 2013

I’ll take the American age.

This evening, we dined on bibimbap and other kimchi-laced foods. My daughter’s school friend and her mother invited us to be their guests at New Seoul, a Korean restaurant in Madison. The owners, close friends of the family, offered us many things to try.

The conversation was light and cheerful with both English and Korean being spoken. The school friend was a gracious nine-year-old translator for my husband and me. Their family originates from Cheongju-si in South Korea.

The friend’s mother asked if I wanted to return to Korea to find my mother. I told her that there would be no way of doing so, but she insisted that I might be able to have DNA testing to find her.

Then, she told us that in Korea, on the day you are born, you are immediately one-year-old! You add a year with each new year. She told of a friend who had her baby on December 31, and on January 1, the baby was considered a two-year-old. In this roulette of birth dates, you really want to be born in the first part of the calendar year.

So, it appears that in Korea, I am 47. While in the United States, I am 45.

The two smiling third graders decided they wanted their Korean age of 11.

Me? I’ll take the American age, thank you.

The conversation was light and cheerful with both English and Korean being spoken. The school friend was a gracious nine-year-old translator for my husband and me. Their family originates from Cheongju-si in South Korea.

The friend’s mother asked if I wanted to return to Korea to find my mother. I told her that there would be no way of doing so, but she insisted that I might be able to have DNA testing to find her.

Then, she told us that in Korea, on the day you are born, you are immediately one-year-old! You add a year with each new year. She told of a friend who had her baby on December 31, and on January 1, the baby was considered a two-year-old. In this roulette of birth dates, you really want to be born in the first part of the calendar year.

So, it appears that in Korea, I am 47. While in the United States, I am 45.

The two smiling third graders decided they wanted their Korean age of 11.

Me? I’ll take the American age, thank you.

Labels:

American age,

bibimbap,

Cheongju-si,

DNA,

English,

Korean,

Korean age,

Madison,

New Seoul Korean restaurant,

translator

16 January 2013

The Perceived Beauty

Here’s a take away on the modeling industry.

The modeling industry is predominately very young, white girls. What does that say to our racially diverse, beautiful young women? What has it told the rest of the world? What do we value?

Feel free to comment on this recent TED talk.

15 January 2013

The Ideal Beauty

Catching up on my podcasts, I heard the most disturbing introduction on This American Life. (This post will address the first 8 minutes of the podcast.)

Teaching at a Korean high school for girls, a young American woman expressed her shock at the vagaries of the Korean teenage girl. While teens everywhere are preoccupied with their appearances, these teens were preoccupied with the ideal beauty they saw in the Western woman.

As I have mentioned here, I, too, wanted the large Western eyes. So much so, I would paint liquid eye-liner on my lids to create a crease … a crease that these young Koreans want so badly that they undergo plastic surgery. My obsession with my eyes was rooted in my desire to blend into my Western society. Or so I thought.

For these girls, they are surrounded by other Koreans, and yet, they believe the thin, pale waif of a girl in all the Western ads is the epitomé of beauty. They believe it, just as their school master does. He believes these girls should stay thin and places scales on every floor of the building. The girls ceremoniously check their weight throughout the day. If they keep their collective weight down, they will earn a cafe!

The more I listened to the Korean girls, the more I wanted to shake them and say, “Cut it out! You are beautiful!” But the same can be said of our Western teenage girls. Ads they see are the same that the Koreans view.

I see our worlds are not so different after all. I see that I was trying to attain what every other young Tennesseean girl wanted … to look like the models that graced the pages of Teen and Seventeen magazine. There were few Asians in those pages from the early 80s … trust me, I searched. Today, there are more ethnic models, but even they are extremely thin with more Western features.

This recent movie, Miss Representation will give you a brief sense of where women and girls stand today. (I suggest you screen this trailer before showing it to your children.)

The media have portrayed women and girls in a way that is virtually impossible in nature. I have vowed to teach my daughter that her beauty comes from within. Superficial beauty does not make one a better friend or partner.

However, in Korea, your superficial beauty may be the difference between getting into college or not. While in the end, the girls brought the young American teacher to understand their desires, I am still shocked and unconvinced.

Teaching at a Korean high school for girls, a young American woman expressed her shock at the vagaries of the Korean teenage girl. While teens everywhere are preoccupied with their appearances, these teens were preoccupied with the ideal beauty they saw in the Western woman.

As I have mentioned here, I, too, wanted the large Western eyes. So much so, I would paint liquid eye-liner on my lids to create a crease … a crease that these young Koreans want so badly that they undergo plastic surgery. My obsession with my eyes was rooted in my desire to blend into my Western society. Or so I thought.

For these girls, they are surrounded by other Koreans, and yet, they believe the thin, pale waif of a girl in all the Western ads is the epitomé of beauty. They believe it, just as their school master does. He believes these girls should stay thin and places scales on every floor of the building. The girls ceremoniously check their weight throughout the day. If they keep their collective weight down, they will earn a cafe!

The more I listened to the Korean girls, the more I wanted to shake them and say, “Cut it out! You are beautiful!” But the same can be said of our Western teenage girls. Ads they see are the same that the Koreans view.

I see our worlds are not so different after all. I see that I was trying to attain what every other young Tennesseean girl wanted … to look like the models that graced the pages of Teen and Seventeen magazine. There were few Asians in those pages from the early 80s … trust me, I searched. Today, there are more ethnic models, but even they are extremely thin with more Western features.

This recent movie, Miss Representation will give you a brief sense of where women and girls stand today. (I suggest you screen this trailer before showing it to your children.)

The media have portrayed women and girls in a way that is virtually impossible in nature. I have vowed to teach my daughter that her beauty comes from within. Superficial beauty does not make one a better friend or partner.

However, in Korea, your superficial beauty may be the difference between getting into college or not. While in the end, the girls brought the young American teacher to understand their desires, I am still shocked and unconvinced.

Labels:

appearances,

beauty,

girls,

high school,

Korean,

media,

Miss Representation,

teenagers,

This American Life,

Western,

wider eyes,

women

13 January 2013

Undercover Adoptee

Yesterday morning at breakfast, I heard this Story Corps taping (before you continue, you might want to listen).

This dialogue between a mother and daughter will surprise you when you reach the end. In less than three minutes we discover the mother was adopted but did not discover this until adulthood.

This 2012 was a year of discovery in my adoption story, but mine focused on the discovery of other adoptees.

Up until this year, I wandered around believing that I was quite alone and undercover. Every now and then, my secret identity would need verification through statements like, “I have no medical family history because I’m adopted.” and “Well, that isn’t really my birthday, it was given to me by the Korean government.”

As I have mentioned, my life has been recently touched by three Korean adoptees. In a couple of instances, the adoptee knew immediately upon meeting me face to face that I must be adopted … few Koreans have a full Puerto Rican name.

Over the holidays, I had a cookie exchange. While introducing people, a new friend, Amy. (not to be confused with Amy in this post), asked how Miya and I knew one another. We mentioned that our adoption histories were similar. At this, Amy said with a smile, “I’m adopted too!”

Amy is a caucasian woman with blonde hair. Her identity as an adoptee is not written on her face, nor does her name give any indication that she is adopted. Amy, Miya and I started sharing our common frustrations with routine questions like “Do you have any diseases in your family history?”

Like me, Amy lost her adoptive mother too soon. Like me, Amy has a younger sibling who is not only six years younger than her, but the sibling is also the biological child of her adoptive parents.

Unlike me, Amy lost her father to cancer and had a middle brother who was also adopted. She had a sibling with whom she could confide as well as share her adoption questions as they became older.

Amy is an art teacher. It is our love of art education that brought us together. When she began teaching, she spoke with her adopted brother about her fear that any of the children she was teaching could, in fact, be biologically related to her. Being so close to her birthplace and much like the adoption story in Story Corps, there was the possibility that those whose social circles intersected hers could be biologically related to her. Her brother assured her that she would be a fabulous teacher regardless of the background of her students.

Amy shares the deep love of her adoptive family that I do, but now I see another side of adoption. Those adoptions that are not international pose completely different questions and challenges. When you aren’t racially different from your family, you are undercover. My race has helped me find others like me, albeit some 40 years into my life, but for Amy and the woman in the Story Corps article, no one assumes that they are adopted.

This year has brought me rich relationships with people who share my adoption experience. I am truly grateful for these friendships. While we are all adopted, each of our stories varies and flows in differing ways, but we all can relate to one another in a way that others cannot. With one another, we are no longer undercover.

Labels:

adopted,

adoptee,

adoption,

alike,

alone,

biological child,

birthdate,

children,

daughter,

family history,

mother,

Native American,

Puerto Rican,

Puerto Rico,

siblings,

Story Corps

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)